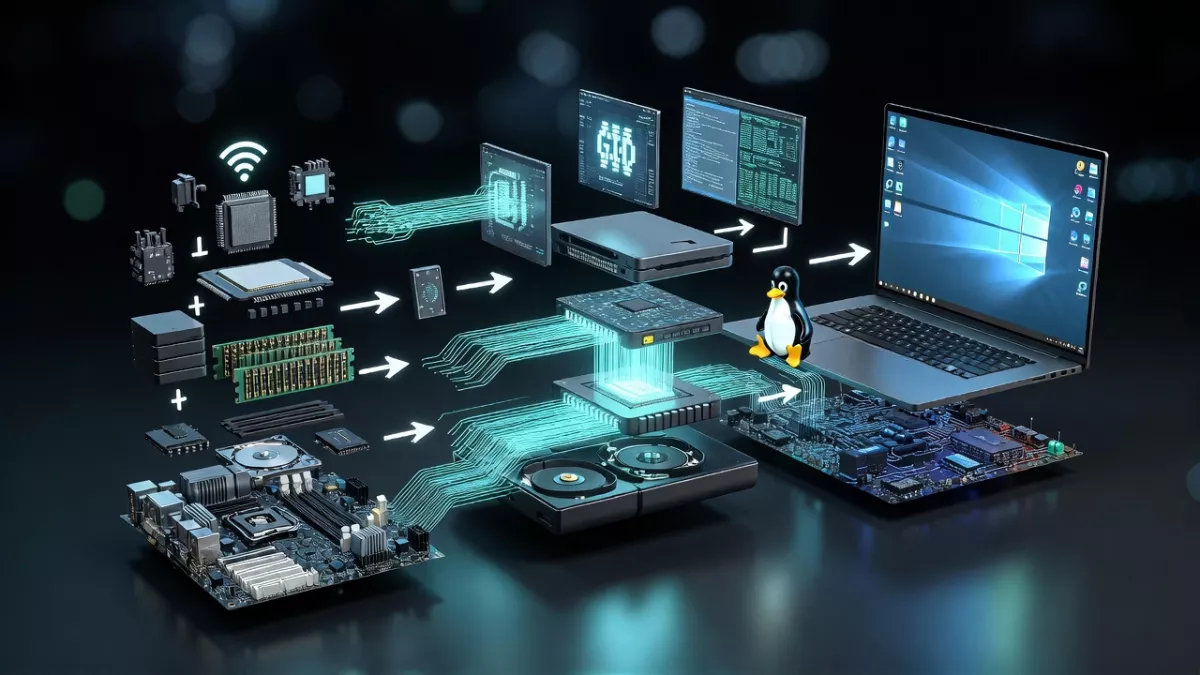

Learn Linux Process Scheduler: how processes are created, scheduled, and managed. Explore CFS, real-time policies, and context switching

Are you curious about how Linux manages multiple programs running simultaneously? If you’ve ever wondered how your system decides which process gets the CPU at a given time, you’re about to discover the fascinating world of the Linux Process Scheduler. In this article, we’ll break it down step by step, explain its importance, and help you understand how Linux keeps everything running smoothly.

What is a Linux Process Scheduler?

The Linux Process Scheduler is the component of the Linux kernel responsible for deciding which process runs at any given moment. Think of it as a traffic controller for your CPU — it ensures that every process gets a fair share of processing power and that critical tasks are prioritized.

Every program or task in Linux is represented as a process, and since CPUs can only execute one instruction at a time per core, the scheduler plays a crucial role in multitasking. Without it, your system could become slow, unresponsive, or chaotic.

Key Functions of the Linux Process Scheduler

The Linux scheduler has several important functions:

- Process Prioritization: Determines which process should run first based on priority levels.

- Time Slicing: Allocates a specific time slot to each process to ensure fair CPU usage.

- Load Balancing: Distributes processes across multiple CPU cores for efficiency.

- Preemption: Interrupts lower-priority tasks to execute higher-priority tasks immediately.

- Fairness: Ensures that no process starves and every process gets CPU time.

Types of Linux Process Schedulers

Linux supports different scheduling algorithms to meet varying system needs. Here are the main types:

1. Completely Fair Scheduler (CFS)

- Default scheduler for Linux since kernel 2.6.23.

- Focuses on fair distribution of CPU time to all processes.

- Uses virtual runtime to track and prioritize tasks.

2. Real-Time Scheduler

- Handles time-sensitive tasks with strict deadlines.

- Supports policies like SCHED_FIFO (first-in-first-out) and SCHED_RR (round-robin).

- Essential for embedded systems, robotics, and real-time applications.

3. Deadline Scheduler

- Ensures tasks meet specific timing constraints.

- Primarily used in high-performance and real-time environments.

How Does Scheduling Affect System Performance?

The efficiency of the Linux scheduler directly impacts:

- System responsiveness: Faster response for interactive applications.

- CPU utilization: Ensures no core remains idle unnecessarily.

- Application performance: Critical processes get prioritized without starving others.

By optimizing scheduling policies, Linux can provide both high performance and fairness, balancing user experience and system efficiency.

Here’s a simple C++ example:

#include

#include

#include

#include

#include

#include

#include

std::mutex coutMutex;

// Function to simulate a CPU-bound task

void cpuTask(int id, int priority) {

// Set thread priority (works on Linux)

sched_param sch;

sch.sched_priority = priority;

if(pthread_setschedparam(pthread_self(), SCHED_FIFO, &sch)) {

std::lock_guard<:mutex> lock(coutMutex);

std::cout << "Failed to set thread priority for thread " << id << "\n";

}

for(int i = 0; i < 5; ++i) {

std::lock_guard<:mutex> lock(coutMutex);

std::cout << "Thread " << id << " running iteration " << i+1 << "\n";

std::this_thread::sleep_for(std::chrono::milliseconds(500)); // Simulate work

}

}

int main() {

std::vector<:thread> threads;

// Create threads with different priorities

threads.emplace_back(cpuTask, 1, 80); // High priority

threads.emplace_back(cpuTask, 2, 50); // Medium priority

threads.emplace_back(cpuTask, 3, 20); // Low priority

// Join threads

for(auto &t : threads) {

t.join();

}

std::cout << "All threads completed!" << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Key Concepts Explained by This Code:

- Threads simulate processes: In Linux, threads are scheduled like processes by the kernel.

- Setting thread priority:

SCHED_FIFOis a real-time scheduling policy (first-in-first-out).- Priority affects which thread gets CPU time first.

- Fair CPU distribution: Even threads with lower priority eventually get CPU time.

- Time slicing simulation:

sleep_for()shows how CPU time is shared among threads.

How to Run:

- Save the file as

scheduler_demo.cpp. - Compile using g++:

g++ -pthread scheduler_demo.cpp -o scheduler_demo - Run with sudo (required for setting real-time priorities):

sudo ./scheduler_demo

Now we break down the C++ code I shared and explain what it does, step by step, in the context of Linux Process Scheduling :

Header Files

#include

#include

#include

#include

#include

#include

#include

iostream→ For printing output to console.thread→ For creating and managing threads (simulating processes).chrono→ For controlling time delays (sleep_forsimulates CPU work).vector→ To store multiple threads.mutex→ To safely print from multiple threads without garbled output.unistd.handpthread.h→ For POSIX thread scheduling and priority manipulation.

Mutex for Safe Printing

std::mutex coutMutex;

- Since multiple threads run simultaneously, printing directly can overlap.

coutMutexensures one thread prints at a time, making output readable.

CPU-Bound Task Function

void cpuTask(int id, int priority) {

sched_param sch;

sch.sched_priority = priority;

if(pthread_setschedparam(pthread_self(), SCHED_FIFO, &sch)) {

std::lock_guard<:mutex> lock(coutMutex);

std::cout << "Failed to set thread priority for thread " << id << "\n";

}

for(int i = 0; i < 5; ++i) {

std::lock_guard<:mutex> lock(coutMutex);

std::cout << "Thread " << id << " running iteration " << i+1 << "\n";

std::this_thread::sleep_for(std::chrono::milliseconds(500));

}

}

What happens here:

- Set thread priority:

sched_param schsets the thread priority.pthread_setschedparamassigns it usingSCHED_FIFO(first-in-first-out real-time policy).- Higher numbers → higher priority.

- Simulate CPU work:

- A

forloop runs 5 iterations. - Each iteration prints which thread is running.

sleep_for(500ms)simulates some CPU time being consumed.

- A

- Safe printing:

lock_guard<:mutex>ensures threads print one by one, preventing mixed output.

Scheduler concept illustrated:

- Threads with higher priority (like 80) are favored by the Linux scheduler.

- Lower priority threads (like 20) may get CPU later, but all threads eventually run, showing fairness.

Main Function

int main() {

std::vector<:thread> threads;

// Create threads with different priorities

threads.emplace_back(cpuTask, 1, 80); // High priority

threads.emplace_back(cpuTask, 2, 50); // Medium priority

threads.emplace_back(cpuTask, 3, 20); // Low priority

// Join threads

for(auto &t : threads) {

t.join();

}

std::cout << "All threads completed!" << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Step-by-step:

- Create threads with priorities:

- Thread 1 → High priority (80)

- Thread 2 → Medium priority (50)

- Thread 3 → Low priority (20)

- Join threads:

t.join()ensures the main program waits until all threads finish.

- Final output:

- After all threads complete their iterations, the program prints:

"All threads completed!"

- After all threads complete their iterations, the program prints:

Linux Scheduler Demonstration:

- High priority threads will often run first.

- Medium and low priority threads get CPU in between based on the scheduling policy.

- You can see time-sharing and fairness in action.

How user-space threads “tell” the CPU to run first and what actually happens in Linux.

User Space Can Only Request Priority

In our C++ code:

pthread_setschedparam(pthread_self(), SCHED_FIFO, &sch);

- This requests the kernel to schedule this thread with a given policy and priority.

- It does not guarantee the CPU will run this thread first.

- The kernel’s scheduler still decides when and for how long each thread gets CPU time.

Think of it like: raising your hand in class — you’re asking for attention, but the teacher decides who speaks first.

How Linux Scheduler Handles It

When a thread requests a scheduling policy/priority:

- The kernel checks the requested policy and priority.

- Example:

SCHED_FIFOthreads with higher priority are favored. - Example:

SCHED_RRthreads get CPU in a round-robin fashion among same-priority threads.

- Example:

- The scheduler decides which thread runs next based on:

- Thread priority

- Current CPU load

- Fairness (in CFS, lower virtual runtime threads run first)

- Core affinity (which CPU cores are available)

- The CPU switches to the selected thread preemptively if needed.

- Higher-priority threads can interrupt lower-priority ones.

Why Our Code “Feels” Like High-Priority Runs First

- Thread 1 has priority 80 (

high), Thread 2 has 50 (medium), Thread 3 has 20 (low). - When these threads are ready, the kernel usually schedules the higher-priority thread first.

- But the kernel still decides, so timing is not guaranteed.

Note: On Linux, changing real-time priorities usually requires

sudobecause user-space cannot normally run high-priority real-time threads without permission.

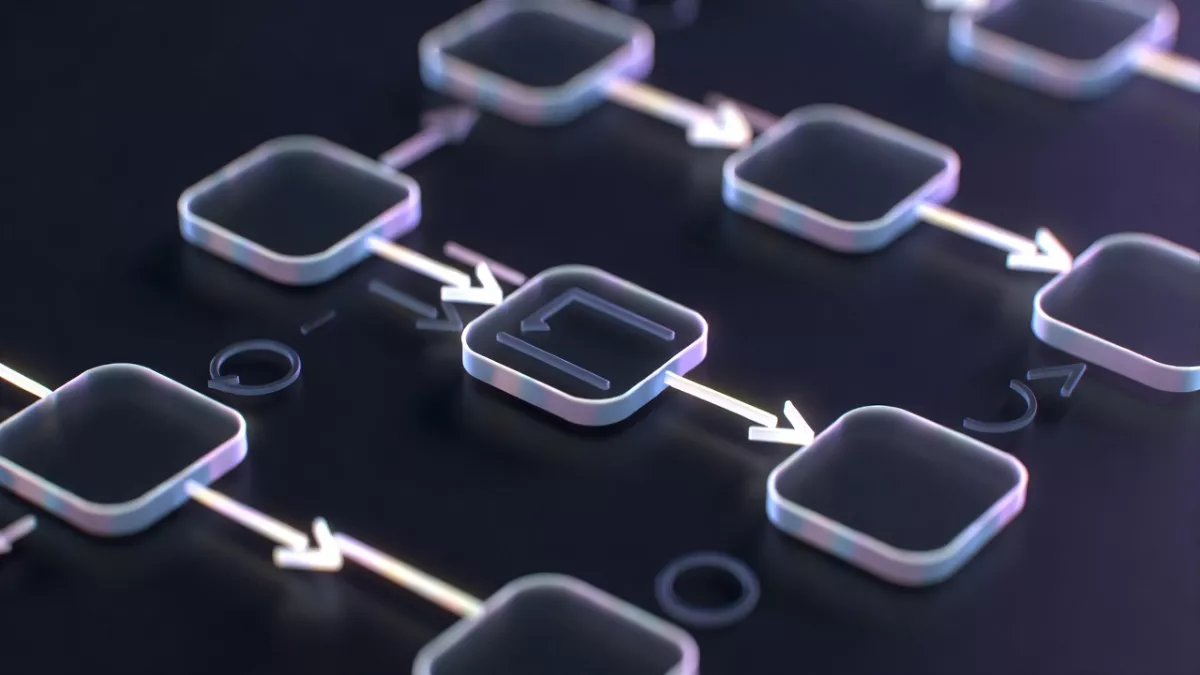

Linux Process Creation and Scheduling Flow

Process Creation (User Request → Kernel)

- You type a command like:

./myprogramin the shell. - The shell calls

fork()system call → creates a child process (a duplicate of itself).- Inside the kernel, a new task_struct is allocated for the process.

task_structcontains process details: PID, scheduling policy, priority, state, etc.

- The child process then calls

execve()→ replaces its memory with the new program (myprogram).- Loads program code from disk into memory.

- Initializes stack, heap, registers.

- Process is now READY to run.

Process States in the Kernel

A process can be in these states:

- NEW → Just created (

fork()called). - READY → Waiting in the runqueue for CPU time.

- RUNNING → Actively executing instructions on a CPU core.

- WAITING / SLEEPING → Waiting for I/O (like reading a file).

- TERMINATED → Finished execution.

The scheduler moves processes between these states.

Scheduler Flow (How CPU Picks a Process)

Linux uses CFS (Completely Fair Scheduler) by default for normal tasks.

High-level flow:

- Runqueue:

Each CPU core has a runqueue (a list of runnable processes). - Pick Next Task:

Scheduler picks the process with the lowest virtual runtime (vruntime) → meaning the one that has had the least CPU time recently. - Context Switch:

- Scheduler saves the current process’s state (registers, stack pointer, program counter).

- Loads the next process’s state.

- CPU starts executing the new process.

- Time Slice / Preemption:

- Each process gets a fair time slice (based on priority/niceness).

- If time slice expires, the scheduler may preempt it and pick another process.

Special Scheduling Classes

Linux supports multiple schedulers depending on policy:

- CFS (SCHED_NORMAL) → Default fair scheduler.

- Real-Time (SCHED_FIFO, SCHED_RR) → For real-time tasks, strictly priority-based.

- Deadline Scheduler (SCHED_DEADLINE) → For tasks with deadlines.

Detailed Response Flow (Step by Step)

Here’s the entire flow from process creation to CPU execution:

- User runs program → shell calls

fork()→ kernel creates newtask_struct. - Kernel assigns PID → adds process to runqueue of a CPU.

- Scheduler invoked (either periodically via timer interrupt or when a process yields).

- Kernel picks next process based on scheduling policy:

- For CFS: choose lowest vruntime.

- For RT: choose highest-priority RT task.

- Context switch occurs: save current process state, load new process state.

- CPU executes instructions of chosen process.

- Interrupts & I/O requests may move process back to waiting state.

- When I/O completes → kernel wakes process → adds back to runqueue.

- Steps 3–8 repeat until process calls

exit(). - Kernel cleans up process resources (memory, file descriptors, task_struct).

Visualizing

[User runs program]

↓

fork() + execve()

↓

[Kernel creates task_struct]

↓

Process added to Runqueue (READY state)

↓

[Scheduler picks next process]

↓

Context Switch → Load process state

↓

CPU executes process (RUNNING)

↓

┌─────────────────────────────────────┐

| If timeslice expires → back to READY |

| If I/O requested → go to WAITING |

| If finished → go to TERMINATED |

└─────────────────────────────────────┘

↓

Repeat for all runnable processes

Scheduling flow through code

User-Space Simulation of Scheduling (C++ Example)

This is not the real scheduler, but it helps you “see” the flow:

#include

#include

#include

#include

struct Process {

int pid;

int burstTime;

int remainingTime;

};

// Simple round-robin scheduler simulation

void roundRobinScheduler(std::queue &readyQueue, int timeSlice) {

while (!readyQueue.empty()) {

Process current = readyQueue.front();

readyQueue.pop();

std::cout << "Running process PID " << current.pid << " for ";

int runTime = std::min(timeSlice, current.remainingTime);

std::cout << runTime << " ms\n";

std::this_thread::sleep_for(std::chrono::milliseconds(runTime));

current.remainingTime -= runTime;

if (current.remainingTime > 0) {

std::cout << "Process PID " << current.pid

<< " back to READY queue with "

<< current.remainingTime << " ms left\n";

readyQueue.push(current); // back to queue

} else {

std::cout << "Process PID " << current.pid << " finished execution!\n";

}

}

}

int main() {

std::queue readyQueue;

// Create 3 processes with different burst times

readyQueue.push({1, 10, 10});

readyQueue.push({2, 5, 5});

readyQueue.push({3, 7, 7});

int timeSlice = 3; // each process gets 3 ms CPU time

roundRobinScheduler(readyQueue, timeSlice);

std::cout << "All processes completed!\n";

return 0;

}

What this shows:

readyQueue→ simulates the kernel’s runqueue.roundRobinScheduler→ picks processes in FIFO order, runs them for a time slice, then puts them back if not finished.- Shows transitions: READY → RUNNING → (READY or TERMINATED).

- Output will look like how the kernel “time-slices” processes.

Kernel-Level Pseudo-Code (Real Flow in Linux)

Inside Linux kernel (kernel/sched/core.c), the scheduling flow looks like this (simplified):

// Called whenever scheduler needs to pick next process

schedule() {

struct task_struct *prev, *next;

prev = current; // process currently running

put_prev_task(prev); // save its state

// Pick the next task from runqueue

next = pick_next_task(rq);

if (next != prev) {

context_switch(prev, next);

}

}

And the CFS Scheduler (pick_next_task) looks like:

pick_next_task(struct rq *rq) {

// CFS stores tasks in a red-black tree ordered by vruntime

// vruntime = "virtual runtime", tracks how much CPU each task used

struct sched_entity *se = leftmost_entity(rq->cfs.rb_root);

return task_of(se); // process with least CPU time

}

What this shows:

schedule()is the heart of Linux scheduling.- The runqueue (

rq) holds all runnable tasks. pick_next_task()→ chooses the process with lowest vruntime (fair scheduling).context_switch()→ performs the actual switch: save old process state, load new one.

Flow with Code Context

- Process created (

fork() + execve()) → kernel makes atask_struct. - Added to runqueue (

enqueue_task). - Timer interrupt or event calls

schedule(). pick_next_task()chooses process (CFS or RT).context_switch()→ CPU starts executing new process.- When timeslice ends or process blocks → back to READY state.

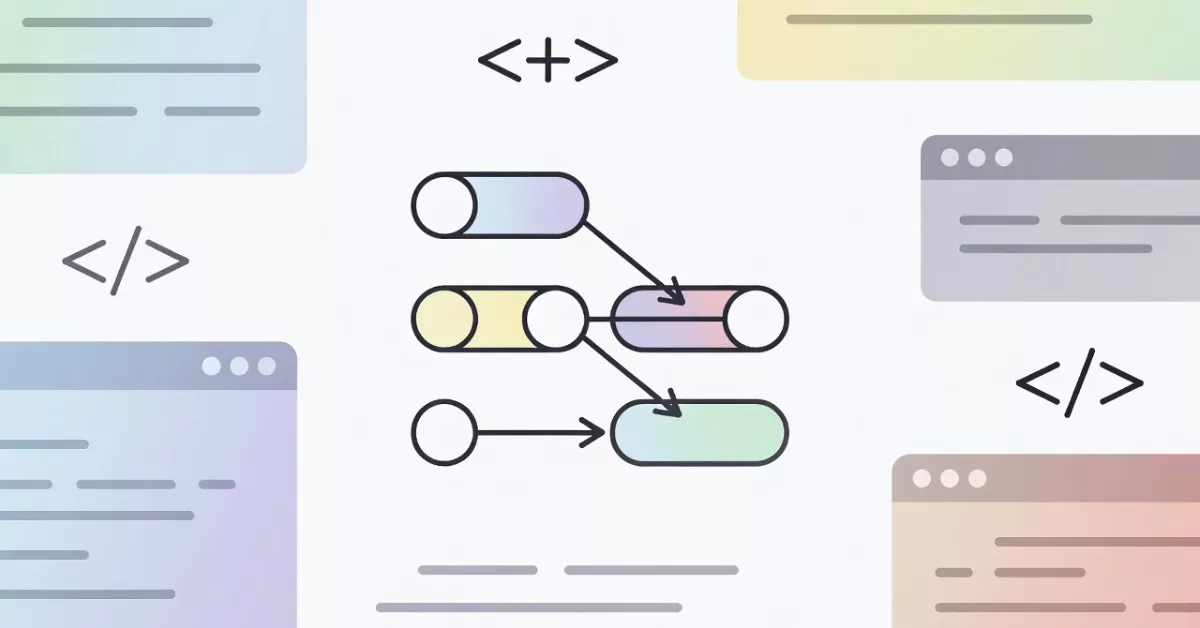

Mapping C++ Simulation ↔ Linux Kernel Scheduler

Process Creation

C++ Simulation:

readyQueue.push({1, 10, 10});

- You manually create processes (PID, burst time).

Linux Kernel:

fork() + execve()

- Kernel creates a new

task_struct. - Loads program into memory.

- Adds it to CPU’s runqueue.

Ready Queue

C++ Simulation:

std::queue readyQueue;

- A simple FIFO queue for processes waiting for CPU.

Linux Kernel:

struct rq {

struct cfs_rq cfs; // Red-black tree of tasks (CFS)

};

- Each CPU has a runqueue (

rq). - Tasks stored in red-black tree, sorted by vruntime (fairness).

Scheduler Decision

C++ Simulation:

Process current = readyQueue.front();

readyQueue.pop();

- Picks the first process in queue.

Linux Kernel:

next = pick_next_task(rq);

- Picks task with smallest vruntime (least CPU so far).

- Ensures fairness.

Process Execution

C++ Simulation:

int runTime = std::min(timeSlice, current.remainingTime);

std::this_thread::sleep_for(std::chrono::milliseconds(runTime));

- Simulates the process “running” for a time slice.

Linux Kernel:

context_switch(prev, next);

- Saves current process registers, stack, PC.

- Loads next process’s state.

- CPU runs the new process until time slice expires or it blocks.

Returning to Ready Queue

C++ Simulation:

if (current.remainingTime > 0) {

readyQueue.push(current);

}

- If process not finished → back to queue.

Linux Kernel:

enqueue_task(rq, task);

- If process not finished → put back in runqueue with updated vruntime.

Process Exit

C++ Simulation:

std::cout << "Process PID " << current.pid << " finished execution!\n";

- Prints when process completes.

Linux Kernel:

do_exit();

release_task();

- Kernel cleans up memory, closes files, removes

task_struct.

Visual Diagram

User Program (C++ Simulation) Linux Kernel Scheduler (Real)

Create process manually fork() + execve()

│ │

Push into readyQueue enqueue_task(runqueue)

│ │

Pop process from queue pick_next_task()

│ │

Simulate run (sleep_for) ←──────→ context_switch()

│ │

If not finished → push back enqueue_task(rq, task)

If finished → print done do_exit(), cleanup

FAQs About Linux Process Scheduler

1.What is the Linux Process Scheduler?

Ans: The Linux Process Scheduler is a kernel component responsible for deciding which process runs on the CPU and when. It manages CPU time fairly among processes, supports multitasking, and ensures real-time tasks get priority when needed.

2.How does the Linux scheduler work?

Ans: The Linux scheduler works by:

Placing processes into run queues.

Choosing the highest priority process (based on policy like CFS, FIFO, or RR).

Assigning CPU time to that process.

Performing context switching when another process needs to run.

This ensures fairness, efficiency, and responsiveness.

3.What are the types of Linux scheduling policies?

Ans: Linux supports multiple scheduling policies:

CFS (Completely Fair Scheduler) → Default, balances CPU fairly among tasks.

SCHED_FIFO → Real-time, runs highest-priority task until it blocks or finishes.

SCHED_RR → Real-time, round-robin scheduling among tasks with the same priority.

SCHED_DEADLINE → For time-critical tasks with deadlines.

4.How does Linux create and schedule a process?

Ans: The flow is:

User calls fork() or clone() → creates a new process.

Kernel assigns a PID and creates a task_struct for the new process.

Process is placed in the ready queue.

Scheduler picks the next process based on priority and policy.

CPU executes that process.

5.What is task_struct in Linux scheduling?

Ans: task_struct is the kernel’s internal data structure that represents each process.

It contains details like:

PID (Process ID)

Scheduling policy (CFS, FIFO, etc.)

Priority

CPU registers

Memory info

The scheduler uses this structure to make decisions.

6.What is context switching in Linux?

Ans: Context switching happens when the scheduler pauses one process and starts another.

The kernel saves the state (CPU registers, stack, program counter) of the current process and loads the state of the next one. This allows multitasking without processes interfering.

7.How does Linux scheduler handle real-time tasks?

Ans: Real-time tasks use SCHED_FIFO or SCHED_RR.

They always run before normal CFS tasks if ready.

Highest-priority real-time process gets CPU time until it blocks or finishes.

This ensures deterministic response for critical applications like audio/video processing or robotics.

8.Can I control process scheduling from user space?

Ans: Yes You can influence scheduling from user space using system calls like:sched_setscheduler() → set scheduling policy.nice() → adjust process priority (for normal tasks).chrt command → change real-time priorities.

However, full control is only possible in kernel space.

9.What is the difference between CFS and Real-time scheduling?

Ans: CFS (Completely Fair Scheduler) → Tries to share CPU time fairly among all tasks.

Real-time (FIFO/RR) → Always prioritizes the most important tasks, fairness is secondary.

10.Why is Linux scheduler important?

Ans: The Linux scheduler is important because it ensures:

Efficient CPU utilization

Fairness among processes

Responsiveness for real-time apps

Smooth multitasking

Without it, processes would starve or the system would freeze under load.

You can also Visit other tutorials of Embedded Prep

- Multithreading in C++

- Multithreading Interview Questions

- Multithreading in Operating System

- Multithreading in Java

- POSIX Threads pthread Beginner’s Guide in C/C++

- Speed Up Code using Multithreading

- Limitations of Multithreading

- Common Issues in Multithreading

- Multithreading Program with One Thread for Addition and One for Multiplication

- Advantage of Multithreading

- Disadvantages of Multithreading

- Applications of Multithreading: How Multithreading Makes Modern Software Faster and Smarter”

- Master CAN Bus Interview Questions 2025

- What Does CAN Stand For in CAN Bus?

- CAN Bus Message Filtering Explained

- CAN Bus Communication Between Nodes With Different Bit Rates

- How Does CAN Bus Handle Message Collisions

- Message Priority Using Identifiers in CAN Protocol

Mr. Raj Kumar is a highly experienced Technical Content Engineer with 7 years of dedicated expertise in the intricate field of embedded systems. At Embedded Prep, Raj is at the forefront of creating and curating high-quality technical content designed to educate and empower aspiring and seasoned professionals in the embedded domain.

Throughout his career, Raj has honed a unique skill set that bridges the gap between deep technical understanding and effective communication. His work encompasses a wide range of educational materials, including in-depth tutorials, practical guides, course modules, and insightful articles focused on embedded hardware and software solutions. He possesses a strong grasp of embedded architectures, microcontrollers, real-time operating systems (RTOS), firmware development, and various communication protocols relevant to the embedded industry.

Raj is adept at collaborating closely with subject matter experts, engineers, and instructional designers to ensure the accuracy, completeness, and pedagogical effectiveness of the content. His meticulous attention to detail and commitment to clarity are instrumental in transforming complex embedded concepts into easily digestible and engaging learning experiences. At Embedded Prep, he plays a crucial role in building a robust knowledge base that helps learners master the complexities of embedded technologies.