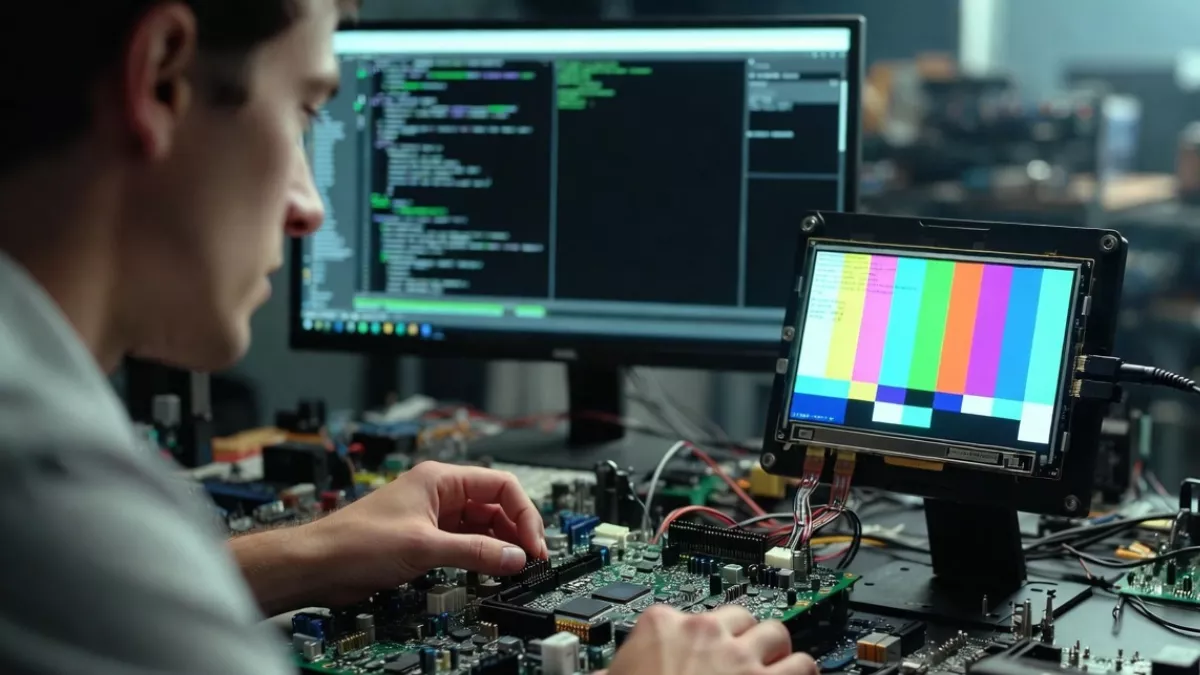

Learn how to modify kernel sources step-by-step, with real driver examples and beginner-friendly guidance for Linux and embedded systems.

If you’ve ever wondered what really happens inside Linux when hardware talks to software, you’re already thinking in the right direction. Modifying kernel sources is where Linux stops being just an operating system and starts becoming a tool you can shape.

This guide is written for curious beginners. You don’t need to be a kernel wizard. You don’t need to memorize internal APIs. You just need patience, basic Linux knowledge, and the willingness to learn by doing.

By the end of this article, you’ll clearly understand how to modifying kernel sources, why people do it, and how to do it safely without breaking your system.

What Does Modifying Kernel Sources Really Mean?

At a simple level, modifying kernel sources means changing the Linux kernel’s source code to adjust how the system behaves.

This could mean:

- Adding support for new hardware

- Tweaking existing drivers

- Adding logs for debugging

- Changing scheduling or memory behavior

- Learning kernel internals for career growth

You’re not rewriting Linux from scratch. Most changes are small and focused. A few lines added. A condition adjusted. A feature enabled or disabled.

That’s how everyone starts.

Why Would Anyone Modify Kernel Sources?

This is the first question beginners ask. And it’s a fair one.

Here are the real reasons people modify kernel sources:

1. Hardware Support

Maybe your device isn’t fully supported by the stock kernel. Embedded boards, sensors, custom peripherals often need kernel tweaks.

2. Learning Kernel Internals

There’s no better way to understand the Linux kernel than reading and modifying its code. Tutorials help, but hands-on experience sticks.

3. Debugging System Issues

Sometimes logs aren’t enough. Adding custom debug prints inside kernel code helps trace tricky bugs.

4. Performance Optimization

In embedded and real-time systems, small kernel changes can make a big difference.

5. Career Growth

If you’re aiming for roles in embedded Linux, BSP development, or kernel engineering, knowing how to modifying kernel sources is a serious advantage.

Before You Touch Kernel Code: Important Basics

Let’s slow down for a moment.

Modifying kernel sources is powerful, but careless changes can:

- Prevent your system from booting

- Break drivers

- Cause silent bugs

So before editing anything, make sure you understand these basics.

You Should Be Comfortable With:

- Basic Linux commands

- Using a terminal

- Editing files with

vimornano - Understanding C code at a basic level

You don’t need to be a C expert. You just need to read code without panicking.

Getting the Linux Kernel Source Code

You can’t modify what you don’t have.

Option 1: Download From kernel.org

This is the clean, official source.

wget https://cdn.kernel.org/pub/linux/kernel/v6.x/linux-6.6.tar.xz

tar -xf linux-6.6.tar.xz

cd linux-6.6

Option 2: Use Git (Recommended)

Git makes experimentation safer.

git clone https://git.kernel.org/pub/scm/linux/kernel/git/stable/linux.git

cd linux

Using Git allows you to:

- Track changes

- Revert mistakes

- Understand diffs clearly

If you’re serious about modifying kernel sources, Git is your friend.

Understanding the Kernel Source Tree (Without Getting Lost)

At first glance, the kernel directory looks scary. Relax. You don’t need to understand everything.

Here are the most important directories:

arch/

Architecture-specific code (ARM, x86, RISC-V)

drivers/

Device drivers (GPIO, I2C, SPI, USB, audio, network)

fs/

File systems (ext4, proc, sysfs)

kernel/

Core kernel logic (scheduler, timers, workqueues)

include/

Header files used across the kernel

When learning how to modifying kernel sources, you’ll usually work inside drivers/ or kernel/.

Start Small: The Best Way to Modify Kernel Sources

Beginners often make the same mistake: trying to change something big.

Don’t.

Start small. Very small.

Best Beginner Modifications

- Add

pr_info()logs - Modify an existing driver slightly

- Change default values

- Add a simple kernel parameter

These teach you the workflow without risk.

Example 1: Adding a Debug Log to Kernel Code

Let’s say you want to see when a function runs.

Open a kernel file, for example:

drivers/base/core.c

Add a log:

#include <linux/printk.h>

pr_info("Kernel core function executed\n");

Rebuild the kernel, boot it, and check:

dmesg | grep Kernel

That’s it.

You just modified kernel sources successfully.

This is exactly how to modifying kernel sources in real life: small, intentional changes.

Kernel Configuration Matters More Than You Think

Many beginners modify code but forget configuration.

Kernel features are controlled by .config.

Run:

make menuconfig

Here you can:

- Enable or disable drivers

- Turn debugging options on

- Control kernel behavior

Sometimes, you don’t need to modify source code at all. A config change is enough.

But when config isn’t enough, source modification comes into play.

Rebuilding the Kernel After Modifications

After modifying kernel sources, you must rebuild.

Basic Build Steps

make -j$(nproc)

make modules

make modules_install

make install

On embedded systems, you’ll usually cross-compile instead.

Take your time here. Build errors are normal. They’re part of learning.

Booting Your Modified Kernel Safely

Never overwrite your working kernel without a backup.

Best Practices:

- Keep old kernel entries in GRUB

- Test on a virtual machine first

- Use a development board, not production hardware

If the system fails to boot, you can always select the older kernel.

This safety net makes modifying kernel sources stress-free.

Common Mistakes Beginners Make

Let me save you some frustration.

1. Editing Without Understanding Context

Always read surrounding code before modifying anything.

2. Ignoring Kernel Logs

dmesg is your best debugging tool.

3. Making Multiple Changes at Once

Change one thing. Test. Then move forward.

4. Skipping Version Control

Always commit changes. Even bad ones.

How to Modifying Kernel Sources for Drivers

Drivers are the most beginner-friendly area.

Typical Driver Modifications:

- Add support for new hardware IDs

- Change probe behavior

- Add logging

- Fix initialization order

If you’re into embedded systems, this is where you’ll spend most of your time.

Understanding how to modifying kernel sources in drivers opens doors to BSP development and low-level debugging.

Debugging Kernel Modifications

Kernel debugging is different from user-space debugging.

Tools You’ll Use:

dmesgprintk/pr_debugdynamic_debug- Kernel panic messages

Start with logs. Logs solve most problems.

Performance and Safety Considerations

Every kernel change affects the whole system.

Keep in mind:

- Avoid infinite loops

- Be careful with memory allocation

- Never sleep in atomic context

- Respect locking rules

You don’t need to master all this now. Just be aware.

Learning Path After Your First Kernel Modification

Once you’re comfortable with basic changes, move forward step by step.

Next Things to Learn:

- Writing a simple kernel module

- Understanding kernel synchronization

- Device tree basics

- Sysfs interfaces

- Debugfs usage

Each builds naturally on modifying kernel sources knowledge.

Is Modifying Kernel Sources Required for Everyone?

No. And that’s okay.

If you’re doing:

- Application development

- Web development

- Simple scripting

You may never need it.

But if you’re in:

- Embedded systems

- Linux system programming

- BSP or driver development

Then learning how to modifying kernel sources is almost unavoidable.

Real-World Advice From Experience

Kernel development isn’t about genius. It’s about patience.

You will:

- Break builds

- Trigger warnings

- Cause crashes

That’s normal.

Every kernel developer you admire has been there.

The key is to:

- Read code slowly

- Change less

- Test more

- Learn from failures

What the Linux Kernel Actually Is ?

Think of the Linux kernel as a middleman.

- Hardware speaks in signals and registers

- Applications speak in files, processes, sockets

- The kernel translates between the two

When you press a key, save a file, or play audio, the kernel is involved.

So when we talk about modifying kernel sources, we mean:

Changing how this middleman behaves.

Not rewriting Linux.

Not breaking everything.

Just changing behavior where needed.

What Does “Kernel Source Code” Mean in Simple Words?

Linux is open source. That means:

- The entire kernel is written in C

- You can read it

- You can modify it

- You can rebuild it

Kernel source code is just a huge collection of .c and .h files.

The difference from normal programs is:

- It runs in kernel space

- Mistakes affect the whole system

That’s why we move carefully.

What Does Modifying Kernel Sources Actually Look Like?

This is important.

People imagine kernel modification as something dramatic. In reality, most changes look like this:

- Adding a few lines

- Changing a condition

- Printing debug logs

- Enabling or disabling a feature

Example:

pr_info("Driver initialized successfully\n");

That single line is a kernel source modification.

So yes, you are already capable of doing it.

Why People Modify Kernel Sources (Real Reasons)

Let’s remove theory and talk about real life.

1. Hardware Doesn’t Work Properly

Common in embedded systems.

- GPIO not toggling

- Audio codec not initializing

- I2C device missing

Often the driver exists but needs small changes.

2. Debugging Deep Issues

Sometimes user-space tools can’t tell you what’s wrong.

Kernel logs can.

So you add logging inside the kernel to understand flow.

3. Learning Linux Internals

Reading kernel code teaches:

- Memory management

- Scheduling

- Synchronization

- Driver architecture

Nothing teaches better than touching real code.

4. Career Growth

If you work with:

- Embedded Linux

- BSP

- Automotive Linux

- System software

Knowing how to modifying kernel sources is not optional.

Fear Control: What Happens If You Mess Up?

This fear stops most beginners.

Here’s the reality:

- Kernel code does not magically affect your system until you build and boot it

- You can keep your old kernel

- You can test on VM or dev board

Worst case:

- Kernel doesn’t boot

- You select old kernel and move on

So no, you won’t “destroy Linux forever”.

Getting the Kernel Source (Why Git Is Better)

You have two main ways.

Tar File Method

Simple download and extract. Fine for learning.

Git Method (Better)

Git gives you:

- Change history

- Diff view

- Easy rollback

- Patch creation

When modifying kernel sources seriously, Git becomes essential.

You’ll often do:

git diff

git status

git checkout .

These commands save lives.

Understanding the Kernel Directory Structure (Without Panic)

At first, the kernel source looks like chaos.

It’s not.

It’s organized by responsibility.

drivers/

This is where most beginners start.

- GPIO

- I2C

- SPI

- Audio

- USB

- Network

If hardware is involved, it’s probably here.

arch/

CPU-specific code.

ARM code is different from x86.

You usually don’t touch this early on.

kernel/

Core logic:

- Scheduling

- Threads

- Timers

- Workqueues

Advanced, but very educational.

fs/

File systems.

include/

Header files shared across the kernel.

The Right Way to Start Modifying Kernel Sources

This is critical advice.

Never start by adding features.

Start by observing behavior.

Step 1: Read the Code

Before editing:

- Read function names

- Read comments

- Understand flow

Step 2: Add Logs

Logs teach you execution order.

pr_info("Function X entered\n");

Step 3: Build and Test

Only after verifying logs should you change logic.

This is the safest way to learn how to modifying kernel sources.

Kernel Configuration: Why Code Alone Is Not Enough

Many beginners modify code but forget configuration.

The kernel uses Kconfig and .config.

Some code won’t even compile unless enabled.

make menuconfig lets you:

- Enable drivers

- Enable debug features

- Control kernel behavior

Sometimes:

- You don’t need code changes

- You just need config changes

Understanding this saves days of confusion.

Building the Kernel (What’s Really Happening)

When you run:

make

The system:

- Compiles thousands of files

- Links them together

- Produces a kernel image

Build errors are normal.

They mean:

- Syntax issue

- Missing config

- Wrong include

Errors are teachers. Don’t fear them.

Booting the Modified Kernel Safely

Golden rule:

Never remove your working kernel.

Keep:

- Old kernel

- New kernel

GRUB lets you choose.

On embedded boards:

- Keep backup image

- Use recovery mode

This makes experimenting safe.

Driver-Level Kernel Modifications (Beginner Sweet Spot)

If you’re new, drivers are the best place to start.

Why?

- Isolated logic

- Clear entry points

- Hardware-related behavior

Common beginner modifications:

- Add print logs in probe function

- Change initialization order

- Fix timing issues

This is where how to modifying kernel sources becomes practical.

Kernel Debugging: How You Actually Find Problems

Kernel debugging is not like GDB user-space debugging.

Main tools:

dmesgprintk- Kernel panic logs

When something fails:

- Read logs

- Identify last message

- Trace backward

Most kernel bugs are logical, not magical.

Safety Rules You Should Respect (But Not Fear)

Some rules matter:

- Don’t sleep in atomic context

- Lock shared data

- Free allocated memory

- Avoid infinite loops

You don’t need to master these immediately.

You’ll learn them naturally as issues appear.

After Basics: Where Do You Go Next?

Once you’re comfortable:

- Write a simple kernel module

- Add sysfs entries

- Learn device tree basics

- Explore debugfs

- Read existing drivers deeply

Each step builds confidence.

Do You Need to Modify Kernel Sources Always?

No.

Many systems work fine with stock kernel.

But when you need control, performance, or deep debugging, kernel modification becomes unavoidable.

That’s why learning how to modifying kernel sources is a long-term investment.

Real Driver Modification Example

We’ll take a simple, realistic example that mirrors what happens in embedded projects.

Scenario (Very Common in Embedded Systems)

You have:

- An embedded board

- A GPIO-controlled LED

- The GPIO driver exists

- But you want:

- Extra debug logs

- Confirmation that GPIO is initialized correctly

So you decide to modify the GPIO driver source.

Step 1: Identify the Right Driver File

GPIO drivers usually live here:

drivers/gpio/

Let’s assume your platform uses a GPIO controller driver like:

drivers/gpio/gpio-xyz.c

(Exact name depends on SoC, but workflow is identical.)

Step 2: Understand the Driver Structure

Open the file and don’t touch anything yet.

You’ll usually see:

probe()functionremove()function- GPIO operations structure

- Register initialization

Example skeleton:

static int xyz_gpio_probe(struct platform_device *pdev)

{

// resource allocation

// register mapping

// gpiochip registration

return 0;

}

Probe function is key

This runs when the kernel detects the GPIO hardware.

Step 3: Add Debug Logs (Safest First Modification)

Before changing logic, add logs to understand flow.

Modify the probe function

#include <linux/printk.h>

static int xyz_gpio_probe(struct platform_device *pdev)

{

pr_info("XYZ GPIO: probe started\n");

// existing code

pr_info("XYZ GPIO: probe completed successfully\n");

return 0;

}

That’s it.

You’ve modified kernel source code safely.

Step 4: Build and Deploy

Rebuild:

make -j$(nproc)

make modules

make dtbs

Flash kernel and dtb to the board.

Step 5: Verify Using dmesg

After boot:

dmesg | grep GPIO

Expected output:

XYZ GPIO: probe started

XYZ GPIO: probe completed successfully

If you see this, congratulations

You just validated:

- Driver probe executed

- Kernel modification worked

- Deployment pipeline is correct

This is exactly how real kernel debugging starts.

Step 6: Real Logic Modification Example (Small but Meaningful)

Now let’s do a real change, not just logs.

Suppose the GPIO direction is wrongly set by default.

Original code:

gpiochip_add_data(&chip, data);

You want to force a GPIO as output during init.

Modify:

ret = gpiochip_add_data(&chip, data);

if (ret)

return ret;

gpio_direction_output(LED_GPIO, 1);

pr_info("XYZ GPIO: LED GPIO set as output\n");

This is a real driver modification:

- Small

- Targeted

- Hardware-aware

This is how kernel work is actually done in companies.

Step 7: Why This Example Matters

From an interviewer’s perspective, this proves you understand:

- Where drivers live

- What probe does

- How to debug kernel code

- Safe kernel modification workflow

Interview-Focused Kernel Modification Q&A (Real Questions, Real Answers)

Now let’s switch hats.

Imagine you’re in an embedded Linux interview.

These are actual questions interviewers ask.

Q1: What do you mean by modifying kernel sources?

Answer:

Modifying kernel sources means changing the Linux kernel’s C source code to alter or extend kernel behavior, such as fixing drivers, adding debug logs, supporting new hardware, or optimizing system behavior. These changes are rebuilt and deployed as a new kernel image.

Q2: When would you modify kernel code instead of user space?

Answer:

When the issue or feature is related to:

- Hardware initialization

- Device drivers

- Interrupt handling

- Power management

- Performance-critical paths

User space cannot fix problems that originate in kernel space.

Q3: What is the safest way to start kernel modification?

Answer:

Start by:

- Reading the existing code

- Adding debug logs using

pr_infoorprintk - Making small, isolated changes

- Testing one change at a time

This minimizes risk and helps understand execution flow.

Q4: What is the role of the probe function in a driver?

Answer:

The probe function is called when the kernel matches a driver with a device. It is responsible for:

- Allocating resources

- Mapping registers

- Initializing hardware

- Registering the driver with kernel subsystems

Most driver debugging starts in the probe function.

Q5: How do you debug kernel modifications?

Answer:

Common methods include:

- Using

dmesgto read kernel logs - Adding

printkorpr_infostatements - Observing boot logs via serial console

- Checking for kernel warnings or panics

Kernel debugging relies heavily on logging.

Q6: What is the difference between device tree changes and driver changes?

Answer:

- Device tree changes describe hardware configuration like pins, interrupts, and addresses.

- Driver changes modify software logic like initialization sequence or feature handling.

Most embedded issues should first be checked in the device tree.

Q7: Can a wrong kernel modification brick a board?

Answer:

A wrong kernel can prevent boot, but boards are rarely permanently bricked. Keeping:

- A backup kernel

- Recovery method (UART, SD card, fastboot)

makes kernel experimentation safe.

Q8: Why is Git important in kernel development?

Answer:

Git helps:

- Track changes

- Revert mistakes

- Create patches

- Review differences

Kernel development without version control is risky and unprofessional.

Q9: What precautions do you take before modifying kernel code?

Answer:

- Understand hardware and requirements

- Read related code paths

- Enable required kernel config options

- Keep a working kernel backup

- Modify one thing at a time

Q10: How do you explain kernel modification experience in interviews?

Answer (Strong Answer):

“I worked on embedded Linux boards where I modified kernel drivers to debug hardware issues, added logs in probe functions, adjusted initialization logic, and rebuilt and tested kernels using cross-compilation. I followed safe workflows with backups and incremental testing.”

Real I2C Driver Modification

We’ll use a very realistic scenario that happens in embedded projects.

The Scenario (Straight From Real Projects)

You have:

- An embedded Linux board

- An I2C sensor or EEPROM

- The driver exists in the kernel

- But the device:

- Sometimes doesn’t probe

- Or works unreliably at boot

Your task:

Modify the I2C driver to debug and fix the issue.

Step 1: Understand the I2C Stack (Simple Mental Model)

Before touching code, understand the layers.

User Space (i2c-tools, app)

↓

I2C Client Driver (sensor, EEPROM)

↓

I2C Core

↓

I2C Controller Driver

↓

Hardware (SoC I2C)

Most modifications happen in the I2C client driver, not the controller.

Step 2: Locate the I2C Driver Source File

I2C client drivers usually live here:

drivers/i2c/

drivers/i2c/chips/

drivers/i2c/busses/

Example driver:

drivers/i2c/chips/xyz_temp_sensor.c

This file controls how the kernel talks to the I2C device.

Step 3: Identify the Probe Function (Always the Starting Point)

Open the driver and look for:

static int xyz_probe(struct i2c_client *client,

const struct i2c_device_id *id)

This function runs when:

- Kernel detects an I2C device

- Device tree or ACPI matches it

Most I2C issues happen here.

Step 4: Add Debug Logs to Confirm Probe Execution

First modification should always be logging.

Add logs at probe entry

#include <linux/printk.h>

static int xyz_probe(struct i2c_client *client,

const struct i2c_device_id *id)

{

pr_info("XYZ I2C: probe started, addr=0x%x\n", client->addr);

// existing code

pr_info("XYZ I2C: probe completed successfully\n");

return 0;

}

Why this matters:

- Confirms device detection

- Confirms I2C address

- Confirms probe completion

This single change answers 50% of I2C debugging questions.

Step 5: Real Problem: Device Needs Delay Before Register Access

Very common issue.

Some I2C devices:

- Need power stabilization

- Need reset time

- Fail if accessed too early

Original code:

ret = i2c_smbus_read_byte_data(client, REG_ID);

Device fails intermittently.

Step 6: Modify Driver to Add Delay (Real Fix)

Add a small delay before register access.

#include <linux/delay.h>

msleep(20);

ret = i2c_smbus_read_byte_data(client, REG_ID);

if (ret < 0) {

pr_err("XYZ I2C: failed to read ID register\n");

return ret;

}

pr_info("XYZ I2C: device ID read successfully\n");

This is a real, production-grade fix.

You didn’t change architecture.

You respected hardware timing.

Step 7: Improve Error Handling (Interview-Worthy Change)

Many drivers fail silently.

Let’s improve that.

Original:

if (ret < 0)

return ret;

Modified:

if (ret < 0) {

pr_err("XYZ I2C: register read failed, error=%d\n", ret);

return ret;

}

Now debugging future issues becomes easier.

Step 8: Verify Device Tree Is Correct (Critical Step)

Before blaming driver, always verify DT.

Example:

i2c1: i2c@40066000 {

status = "okay";

xyz@48 {

compatible = "vendor,xyz-temp";

reg = <0x48>;

};

};

Driver and DT must match:

compatiblestring- I2C address

Many “driver bugs” are actually DT mistakes.

Step 9: Build and Deploy Modified Kernel

Rebuild kernel and device tree:

make -j$(nproc)

make dtbs

Flash to board.

Step 10: Validate Using i2c-tools and dmesg

On the board:

dmesg | grep XYZ

Expected:

XYZ I2C: probe started, addr=0x48

XYZ I2C: device ID read successfully

XYZ I2C: probe completed successfully

You can also use:

i2cdetect -y 1

This confirms hardware visibility.

Why This Example Is Gold for Interviews

You demonstrated:

- Understanding of I2C architecture

- Proper probe debugging

- Hardware-aware delay handling

- Clean error reporting

- Safe kernel modification workflow

This is exactly what interviewers want.

Bonus: Quick SPI Driver Modification Comparison

SPI drivers are similar but with differences.

SPI probe function:

static int xyz_spi_probe(struct spi_device *spi)

Common SPI modification:

- Adjust SPI mode

- Set max speed

- Fix chip select behavior

Example:

spi->mode = SPI_MODE_0;

spi->max_speed_hz = 1000000;

spi_setup(spi);

Same workflow. Different bus.

Common Beginner Mistakes in I2C/SPI Modifications

Avoid these:

- Ignoring device tree

- Modifying controller instead of client

- Not checking return values

- Adding delays blindly without reason

- Changing multiple things at once

Kernel Configuration and Compilation

If you work with Linux at anything below the application layer, sooner or later you run into one unavoidable topic: kernel configuration and compilation. It sounds heavy. It sounds scary. And honestly, most tutorials make it worse by throwing options, commands, and theory at you without context.

Let’s fix that.

In this guide, we’ll walk through kernel configuration and compilation step by step, in plain language. You’ll understand why we configure the kernel, how compilation actually works, and what matters in real embedded and Linux development. No fluff. No marketing talk. Just real understanding.

What Is Kernel Configuration and Compilation?

At a high level, kernel configuration and compilation is the process of:

- Selecting which features the Linux kernel should include

- Turning that configuration into a binary kernel image

- Installing that kernel so the system can boot with it

The Linux kernel is not a single fixed binary. It’s more like a massive toolkit. You decide what tools you want, and then you build a kernel that fits your system.

This is especially important for:

- Embedded boards

- Custom hardware

- Performance-sensitive systems

- Learning kernel internals properly

Why Kernel Configuration Matters More Than You Think

A common beginner mistake is assuming kernel configuration is optional or something only distro maintainers do. That’s not true.

Here’s why kernel configuration matters:

- Hardware support

The kernel must know which drivers to include for your CPU, storage, display, network, and peripherals. - Boot time and size

Including everything makes the kernel huge and slow. Embedded systems suffer badly from this. - Stability

Wrong options can cause random crashes, boot failures, or subtle bugs. - Security

Unused subsystems increase attack surface.

Kernel configuration is about control. Compilation is just the final step.

Understanding the Linux Kernel Source Tree

Before touching configuration, you need to understand what you’re configuring.

When you download Linux kernel source, you’ll see directories like:

arch/– architecture-specific code (ARM, x86, RISC-V)drivers/– device driversfs/– file systemskernel/– core kernel logicnet/– networking stackinclude/– header files

Kernel configuration doesn’t modify these files directly. Instead, it decides which parts get compiled.

That decision lives in a file called .config.

What Is the .config File?

The .config file is the heart of kernel configuration and compilation.

It contains thousands of options like:

CONFIG_USB=yCONFIG_I2C=mCONFIG_PREEMPT=y

Each option tells the build system one of three things:

y– compile it into the kernelm– compile it as a module- not set – don’t include it

Everything you do during kernel configuration ultimately edits this file.

Kernel Configuration Tools Explained Simply

Linux gives you multiple ways to configure the kernel. They all do the same thing: generate a .config file.

1. menuconfig

This is the most popular option and the best for beginners.

It gives you a text-based menu where you can:

- Navigate categories

- Enable or disable features

- Search for specific options

It feels like an old-school BIOS screen, and that’s a good thing.

2. nconfig

Similar to menuconfig, but more keyboard-friendly and modern.

3. xconfig and gconfig

Graphical interfaces using Qt or GTK. These are less common today, especially in embedded workflows.

4. defconfig

This uses a default configuration provided by the kernel or board vendor.

For example:

x86_64_defconfigarm_defconfig

This is often your starting point.

A Practical Kernel Configuration Workflow

Let’s talk about how kernel configuration and compilation actually happens in real projects.

Step 1: Start With a Base Configuration

Never start from scratch unless you enjoy pain.

For desktop systems:

- Use your current kernel config from

/boot/config-*

For embedded boards:

- Use vendor-provided defconfig

- Or

make ARCH=arm defconfig

This ensures basic hardware support is already there.

Step 2: Open the Configuration Menu

Once you have a base config, you refine it.

You usually do this with menuconfig.

Inside the menu, you’ll see categories like:

- Processor type and features

- Device Drivers

- Networking support

- File systems

Don’t randomly toggle options. Always ask:

- Do I need this hardware?

- Will this run as built-in or module?

- Is this required at boot?

Step 3: Understanding Built-in vs Modules

This is one of the most important decisions in kernel configuration.

- Built-in (

y)

Needed for boot-critical components like:- Root filesystem drivers

- Storage controller drivers

- CPU support

- Module (

m)

Good for:- Optional hardware

- USB devices

- Development and debugging

Embedded systems usually prefer built-in drivers for reliability.

Common Kernel Configuration Mistakes Beginners Make

Let’s save you some pain.

Enabling Everything

More features do not mean better kernel. It means:

- Larger image

- Slower boot

- Harder debugging

Disabling Something Without Knowing Dependencies

Kernel options depend on each other. Disabling one thing can silently break another.

Ignoring Architecture Settings

The arch/ configuration is critical. Wrong CPU or memory model means the kernel won’t boot.

From Configuration to Compilation: What Happens Next?

Once the .config file is ready, kernel compilation begins.

Kernel compilation is just a structured build process using:

- GCC or Clang

- Makefiles

- Kbuild system

But under the hood, it’s doing something very logical.

Understanding the Kernel Compilation Process

During kernel compilation:

- The build system reads

.config - It selects which source files to compile

- It compiles them into object files

- It links them into:

vmlinux(uncompressed kernel)bzImage,zImage, orImage(bootable kernel)

The exact output depends on architecture.

This is why kernel configuration and compilation are inseparable. One drives the other.

Kernel Compilation for Embedded Boards

Embedded systems add a few extra steps.

Cross Compilation

Most embedded boards use ARM or RISC-V, not x86.

This means:

- Your compiler runs on x86

- The output runs on ARM

This is called cross compilation.

You must set:

- Architecture

- Cross compiler prefix

If these are wrong, compilation may succeed but the kernel won’t boot.

Device Tree and Kernel Compilation

Modern embedded Linux uses Device Tree.

The kernel is compiled once, but hardware description lives in .dtb files.

Kernel compilation often includes:

- Kernel image

- Device Tree Blob

- Optional initramfs

They work together at boot.

Installing the Compiled Kernel

After successful kernel compilation, you need to install it.

On desktops:

- Kernel image goes to

/boot - Modules go to

/lib/modules/<version>

On embedded systems:

- Kernel image goes to bootloader storage

- Modules go to root filesystem

Installation is where many first-time kernel builders panic. Take it slow.

Verifying Your Kernel Build

Before celebrating, always verify.

Check:

- Kernel version string

- Boot logs

- Loaded modules

- Hardware detection

If something doesn’t work, go back to configuration, not random patches.

Debugging Kernel Configuration and Compilation Issues

When things break, it’s usually due to:

- Missing configuration option

- Wrong built-in vs module choice

- Architecture mismatch

- Toolchain issues

The fix is almost always in the configuration, not the code.

This is why understanding kernel configuration and compilation deeply saves huge amounts of time.

How Kernel Configuration Impacts Performance

Kernel configuration is not just about making it work. It’s about making it work well.

Good configuration can:

- Reduce boot time

- Improve latency

- Lower memory usage

- Improve power efficiency

Bad configuration does the opposite.

This is especially critical in automotive, IoT, and real-time systems.

Real-World Use Case: Why Professionals Care

In real embedded projects:

- Kernel configuration is version-controlled

- Changes are reviewed carefully

- Compilation is automated using CI

Nobody randomly edits the kernel. Every change has a reason.

Learning kernel configuration and compilation puts you closer to professional kernel development.

Interview Perspective: Why This Topic Matters

Interviewers love this topic because it shows depth.

They’re not testing memorization. They want to know:

- Do you understand how Linux boots?

- Can you support new hardware?

- Can you debug low-level issues?

If you can explain kernel configuration and compilation clearly, you stand out immediately.

Best Practices for Kernel Configuration and Compilation

Let’s wrap the technical part with solid habits.

- Always keep your

.configunder version control - Document why options are enabled or disabled

- Start from a known working config

- Change one thing at a time

- Test after every build

These habits matter more than memorizing commands.

Real Kernel Configuration Walkthrough for an ARM Board

Step 1: Set Up the Environment

Before touching the kernel:

- Install required tools on your Linux host (x86 machine):

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt-get install build-essential libncurses-dev bison flex libssl-dev libelf-dev bc

- Install the cross-compiler for ARM (for BeagleBone Black, ARMv7):

sudo apt-get install gcc-arm-linux-gnueabihf

This is important: your host CPU is x86, but the board is ARM. We need a cross-compiler to generate ARM binaries.

Step 2: Get the Kernel Source

Download the kernel source from kernel.org or your board vendor:

wget https://cdn.kernel.org/pub/linux/kernel/v6.x/linux-6.6.tar.xz

tar -xvf linux-6.6.tar.xz

cd linux-6.6

Now you’re in the Linux source tree.

Step 3: Start With a Base Configuration

Boards usually provide a defconfig, a default config for the hardware. For BeagleBone Black:

make ARCH=arm CROSS_COMPILE=arm-linux-gnueabihf- am335x_boneblack_defconfig

ARCH=armtells the kernel you’re building for ARM architectureCROSS_COMPILE=arm-linux-gnueabihf-tells it which compiler to useam335x_boneblack_defconfigis the board’s default configuration

This generates a .config file in the source directory.

Step 4: Customize Configuration

Now, let’s refine it using menuconfig:

make ARCH=arm CROSS_COMPILE=arm-linux-gnueabihf- menuconfig

You’ll see a menu with categories. Here’s what we usually do for BeagleBone Black:

Key Sections to Check:

- Processor Type and Features

- Confirm CPU type: Cortex-A8

- Enable NEON and VFP if using floating-point intensive apps

- Device Drivers → I2C Support

- Enable I2C as built-in or module (

yorm) - Add support for specific devices if needed, e.g.,

I2C_TWL4030for power management

- Enable I2C as built-in or module (

- Device Drivers → SPI Support

- Enable SPI master and relevant SPI devices

- Useful if you plan to connect sensors or displays

- File Systems

- Enable

ext4if your root filesystem uses it - Include

FATorVFATif using SD card support

- Enable

- Networking

- Enable

Ethernet driverfor AM335x PHY - Optional: Wi-Fi or USB network if using modules

- Enable

- USB Support

- Enable USB host controller (

EHCI) for peripherals - Enable USB Gadget if you want the board to act as a device

- Enable USB host controller (

- Kernel Features

- Enable Preemption Model: “Voluntary Preemption” for desktop-like responsiveness, or “No Preemption” for real-time reliability

- Enable initramfs if you plan to embed modules inside kernel

Once done, save .config and exit.

Step 5: Compile the Kernel

Now we build the kernel and modules:

make ARCH=arm CROSS_COMPILE=arm-linux-gnueabihf- zImage modules dtbs -j$(nproc)

zImage– compressed kernel imagemodules– all kernel modules (.ko)dtbs– device tree blobs-j$(nproc)– parallel compilation using all CPU cores

Tip: For embedded boards, compilation can take several minutes to over an hour depending on your PC.

Step 6: Install Modules and Kernel

- Create a folder for modules:

mkdir -p ~/bbb-rootfs/lib/modules

- Copy modules:

make ARCH=arm CROSS_COMPILE=arm-linux-gnueabihf- INSTALL_MOD_PATH=~/bbb-rootfs modules_install

- Copy kernel and device tree:

cp arch/arm/boot/zImage ~/bbb-boot/

cp arch/arm/boot/dts/am335x-boneblack.dtb ~/bbb-boot/

Now your bootloader can load zImage and am335x-boneblack.dtb.

Step 7: Boot and Verify

- Flash the bootloader and root filesystem if not already done.

- Boot the board.

- Check kernel version:

uname -r

- Verify modules:

lsmod

- Check hardware detection:

dmesg | grep i2c

dmesg | grep spi

If everything works, congratulations! You’ve just done kernel configuration and compilation for an ARM board.

Step 8: Common Pitfalls for Beginners

- Wrong cross-compiler → Kernel builds but won’t boot

- Missing essential drivers → Kernel panics on boot

- Wrong device tree → Board boots but peripherals fail

- Forgetting

modules_install→ Modules not available at runtime

Step 9: Tips for Real Embedded Development

- Keep a versioned

.configfile in Git - Test changes incrementally

- Document why you changed any option

- Use a CI system if working on multiple boards or kernels

Optional: Quick SPI/I2C Driver Test

If you enabled I2C or SPI in the kernel:

# List I2C devices

i2cdetect -y 1

# List SPI devices

ls /dev/spidev*

This ensures kernel configuration matches your hardware setup.

FAQ on Kernel Configuration and Compilation

1. What is kernel configuration and compilation in Linux?

Answer:

Kernel configuration and compilation is the process of customizing the Linux kernel for your system by selecting which features, drivers, and modules to include, and then building a binary kernel image that your machine can run. Proper configuration ensures hardware compatibility, better performance, and system stability.

2. Why is kernel configuration important for ARM boards?

Answer:

ARM boards have diverse hardware components like CPUs, I2C, SPI, and USB peripherals. Kernel configuration allows you to include only the necessary drivers and modules, reducing kernel size, improving boot time, and ensuring that all hardware works reliably.

3. How do I start kernel configuration for an embedded board?

Answer:

The easiest way is to start with a defconfig provided by your board vendor. For example, for BeagleBone Black, you can use:make ARCH=arm CROSS_COMPILE=arm-linux-gnueabihf- am335x_boneblack_defconfig

This gives you a solid starting point, which you can further refine using menuconfig or nconfig.

4. What is the difference between built-in and module drivers in kernel configuration?

Answer:

- Built-in (

y): Compiled directly into the kernel; necessary for boot-critical hardware. - Module (

m): Compiled as a loadable kernel module; can be loaded or unloaded at runtime.

Choosing the right type ensures efficient memory usage and system reliability.

5. How do I compile the Linux kernel after configuration?

Answer:

After configuration, use the following command:

make ARCH=arm CROSS_COMPILE=arm-linux-gnueabihf- zImage modules dtbs -j$(nproc)

This builds the kernel image, modules, and device tree blobs for your ARM board.

6. How do I install compiled kernel modules?

Answer:

Use modules_install with an installation path pointing to your root filesystem:

make ARCH=arm CROSS_COMPILE=arm-linux-gnueabihf- INSTALL_MOD_PATH=~/rootfs modules_install

This ensures all required modules are available when the kernel boots.

7. What are the common mistakes to avoid during kernel configuration?

Answer:

- Enabling unnecessary features, which bloats the kernel

- Disabling essential drivers or CPU support

- Using the wrong architecture or cross-compiler

- Forgetting to install modules

Avoiding these mistakes saves hours of troubleshooting.

8. How can I verify my compiled kernel is working correctly?

Answer:

After booting your board with the new kernel, check:

- Kernel version:

uname -r - Loaded modules:

lsmod - Hardware detection:

dmesg | grep i2cordmesg | grep spi

Proper verification ensures the configuration matches your hardware.

9. Can kernel configuration improve system performance?

Answer:

Yes. A well-configured kernel reduces boot time, memory usage, and CPU overhead. By including only necessary features and drivers, you create a lean, fast, and secure kernel optimized for your embedded board.

10. Is kernel configuration and compilation necessary for beginners?

Answer:

Absolutely. Even beginners benefit from learning kernel configuration and compilation. It builds a strong foundation in Linux system programming, helps debug hardware issues, and prepares you for advanced embedded development on ARM or other architectures.

Read More about Process : What is is Process

Read More about System Call in Linux : What is System call

Read More about IPC : What is IPC

Mr. Raj Kumar is a highly experienced Technical Content Engineer with 7 years of dedicated expertise in the intricate field of embedded systems. At Embedded Prep, Raj is at the forefront of creating and curating high-quality technical content designed to educate and empower aspiring and seasoned professionals in the embedded domain.

Throughout his career, Raj has honed a unique skill set that bridges the gap between deep technical understanding and effective communication. His work encompasses a wide range of educational materials, including in-depth tutorials, practical guides, course modules, and insightful articles focused on embedded hardware and software solutions. He possesses a strong grasp of embedded architectures, microcontrollers, real-time operating systems (RTOS), firmware development, and various communication protocols relevant to the embedded industry.

Raj is adept at collaborating closely with subject matter experts, engineers, and instructional designers to ensure the accuracy, completeness, and pedagogical effectiveness of the content. His meticulous attention to detail and commitment to clarity are instrumental in transforming complex embedded concepts into easily digestible and engaging learning experiences. At Embedded Prep, he plays a crucial role in building a robust knowledge base that helps learners master the complexities of embedded technologies.