Learn Drivers in Linux with a beginner-friendly guide covering device driver types, kernel interaction, hardware access, and real-world examples.

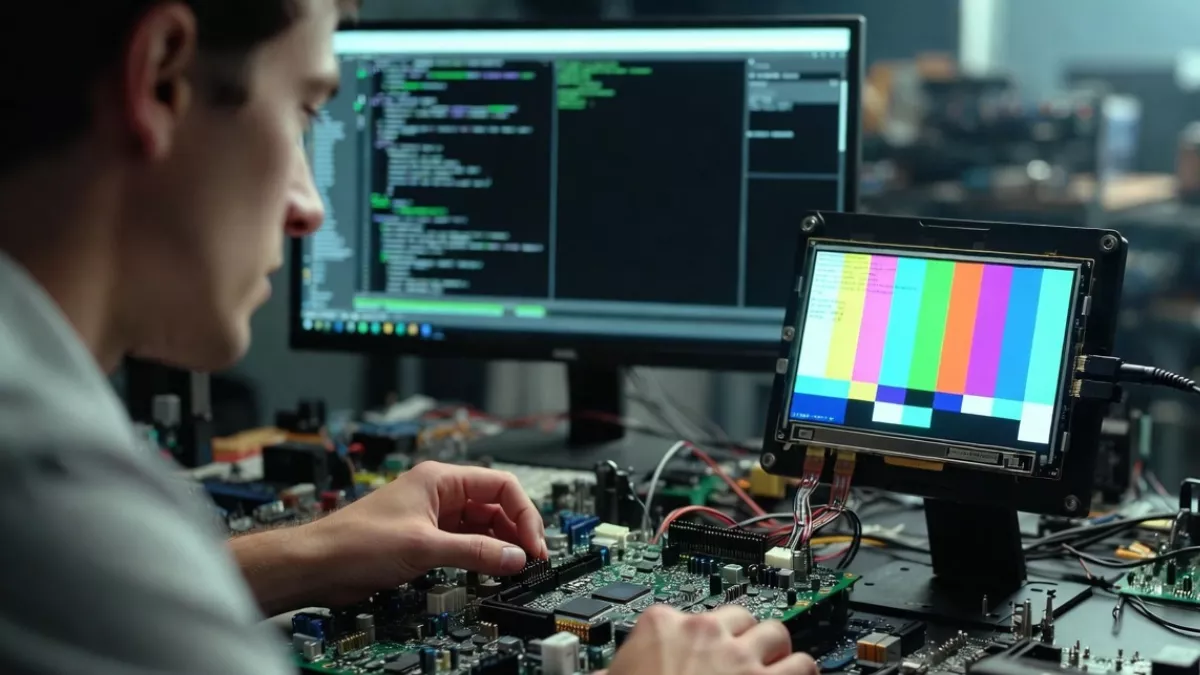

If you’ve ever wondered how Linux communicates with the hardware inside your computer or embedded system, the answer lies in drivers in Linux. Drivers are the bridge between the operating system and the hardware, allowing your software to interact with sensors, displays, motors, and other peripherals seamlessly.

Today, we’ll break down the world of Linux drivers, focusing on three widely used interfaces: I2C, SPI, and GPIO. By the end of this guide, you’ll understand not just what these drivers do, but how they work, why they are important, and how you can interact with them.

What Are Drivers in Linux?

In simple terms, a driver is a piece of software that tells the operating system how to communicate with a piece of hardware. Without drivers, the OS would not know how to operate your keyboard, monitor, Wi-Fi card, or even a simple LED.

Think of a driver as a translator: it translates generic commands from your OS into device-specific instructions. Linux, being open-source, has a robust driver model that supports a wide range of hardware from different manufacturers. Drivers in Linux can be:

- Built-in: Compiled directly into the Linux kernel.

- Loadable Kernel Modules (LKMs): Dynamically loaded into the kernel when needed. This is very common for devices like USB peripherals, I2C sensors, or SPI modules.

Why Drivers in Linux Are Important

Without drivers, your hardware is essentially useless. Let’s take a real-world analogy: imagine having a smartphone without an app that tells it how to read your fingerprint. That’s your hardware without a driver. In Linux:

- Drivers allow communication between hardware and software.

- They manage resources like memory, interrupts, and I/O ports.

- They abstract complex hardware details, making programming simpler.

- They enable modularity — you can add or remove drivers without affecting the entire OS.

Understanding drivers is crucial for embedded systems developers, Linux kernel enthusiasts, and anyone looking to work with hardware on Linux.

Types of Drivers in Linux

Linux drivers can be classified into several categories based on the type of hardware they manage:

- Character Device Drivers: Handle devices that transmit data as a stream of bytes, like serial ports or keyboards.

- Block Device Drivers: Manage devices that store data in blocks, like hard drives and SSDs.

- Network Device Drivers: Control network hardware like Ethernet or Wi-Fi cards.

- Platform Device Drivers: For devices integrated on boards like I2C sensors, SPI modules, and GPIO-controlled peripherals.

For this guide, we’ll focus on drivers in Linux for I2C, SPI, and GPIO, which are crucial in embedded Linux projects.

Understanding I2C in Linux

I2C (Inter-Integrated Circuit) is a communication protocol widely used in embedded systems. It allows multiple devices to communicate using just two wires: SDA (data) and SCL (clock). I2C is perfect for low-speed communication between sensors, EEPROMs, and microcontrollers.

How I2C Works

- The master device initiates communication.

- Each device on the bus has a unique address.

- Data is transmitted in packets, with acknowledgment signals sent back and forth.

- Multiple slaves can share the same bus, but only one master controls the clock.

I2C Drivers in Linux

Linux provides a kernel subsystem for I2C, which handles all the communication details. The main components are:

- I2C adapter driver: Manages the physical bus (hardware-specific).

- I2C client driver: Manages devices connected to the bus, like sensors or EEPROMs.

Example: Interacting with an I2C Device

On Linux, you can interact with I2C devices using:

sudo apt-get install i2c-tools

i2cdetect -y 1

This command scans the I2C bus and lists all connected devices. Writing a driver for an I2C sensor involves registering a client driver that communicates with the sensor using the I2C subsystem APIs.

Understanding SPI in Linux

SPI (Serial Peripheral Interface) is another popular communication protocol. Unlike I2C, SPI uses four wires: MISO, MOSI, SCLK, and CS. SPI is faster than I2C and is often used for displays, memory cards, and high-speed sensors.

How SPI Works

- The master device controls the clock.

- Data is transmitted simultaneously: master out to slave in (MOSI) and slave out to master in (MISO).

- Multiple slaves are supported using separate chip select (CS) lines.

SPI Drivers in Linux

Linux has an SPI subsystem that supports:

- SPI master drivers: Control the SPI bus.

- SPI device drivers: Control the slave devices.

Example: SPI Device Driver

A typical SPI driver in Linux will:

- Register the SPI device with the kernel.

- Implement read/write operations using SPI APIs.

- Handle interrupts or DMA for efficient data transfer.

SPI is preferred when speed is critical, like in ADCs, DACs, or display modules.

Understanding GPIO in Linux

GPIO (General Purpose Input/Output) pins are the most basic way to interact with hardware. You can control LEDs, read buttons, or interface with relays using GPIO.

How GPIO Works

- Each GPIO pin can be configured as input or output.

- Input pins can read signals (like button presses).

- Output pins can drive signals (like turning on an LED).

GPIO Drivers in Linux

Linux exposes GPIO through the GPIO subsystem, which provides:

- sysfs interface: Older method to access GPIO via

/sys/class/gpio/. - Character device interface: Modern method using

/dev/gpiochipX.

Example: Controlling a GPIO Pin

echo 23 > /sys/class/gpio/export

echo out > /sys/class/gpio/gpio23/direction

echo 1 > /sys/class/gpio/gpio23/value

This sequence sets GPIO 23 as an output and turns it on. Writing a proper GPIO driver involves handling pin mapping, interrupts, and edge detection.

Writing Linux Drivers: A Step-by-Step Overview

Writing drivers in Linux might sound complex, but it’s manageable if you understand the structure. Here’s a simplified flow:

- Include Kernel Headers

#include <linux/module.h> #include <linux/kernel.h> #include <linux/init.h> - Initialize the Driver

static int __init my_driver_init(void) { printk(KERN_INFO "Driver loaded successfully\n"); return 0; } - Cleanup on Exit

static void __exit my_driver_exit(void) { printk(KERN_INFO "Driver unloaded\n"); } - Register Driver

module_init(my_driver_init); module_exit(my_driver_exit); MODULE_LICENSE("GPL"); MODULE_AUTHOR("Your Name"); MODULE_DESCRIPTION("Example Linux Driver");

For I2C, SPI, and GPIO, you’d use specific kernel APIs to interact with the respective subsystem.

Debugging Linux Drivers

Once your driver is written, debugging is key. Linux provides multiple tools:

dmesg: View kernel messages.lsmod: List loaded modules.insmod/rmmod: Load and remove modules.strace: Trace system calls.gdborkgdb: Debug kernel code for complex issues.

Best Practices for Linux Drivers

- Always check return values of API calls.

- Use interrupts instead of busy-waiting for efficiency.

- Follow kernel coding standards for readability.

- Modularize your driver to handle multiple devices.

- Ensure thread-safety when accessing shared resources.

Real-World Applications of I2C, SPI, and GPIO Drivers

- I2C: Temperature sensors, EEPROMs, accelerometers, real-time clocks.

- SPI: OLED displays, SD cards, ADC/DAC modules.

- GPIO: LEDs, buttons, relays, buzzers.

Embedded Linux systems like Raspberry Pi, BeagleBone, and custom ARM boards rely heavily on these drivers for their operation.

Step-by-Step Guide: Implementing an I2C Driver in Linux

We’ll create a basic I2C Linux driver that can read/write data from a device and be tested in userspace. I’ll cover:

- Kernel setup

- Writing the driver

- Compiling as a loadable kernel module (LKM)

- Flashing/loading the module

- Testing with a simple userspace program

Step 1: Prepare Your Environment

Before writing an I2C driver, ensure:

- Linux kernel headers are installed.

sudo apt-get install linux-headers-$(uname -r) - Your I2C bus is enabled (especially on embedded boards like Raspberry Pi or BeagleBone).

- On Raspberry Pi, enable via

raspi-config. - On BeagleBone, use Device Tree overlays.

- On Raspberry Pi, enable via

- Install i2c-tools to test the bus:

sudo apt-get install i2c-tools i2cdetect -y 1

This will show connected devices on the I2C bus.

Step 2: Create the Driver Directory

mkdir ~/i2c_driver

cd ~/i2c_driver

We will have:

i2c_driver.c→ Driver source codeMakefile→ Build instructions

Step 3: Write the I2C Driver Code

Here’s a simple example driver for an I2C device:

// i2c_driver.c

#include <linux/module.h>

#include <linux/kernel.h>

#include <linux/init.h>

#include <linux/i2c.h>

#include <linux/slab.h>

#define DEVICE_NAME "my_i2c_device"

#define I2C_BUS_NUM 1 // I2C bus number (change for your hardware)

#define I2C_ADDR 0x48 // I2C slave device address

static struct i2c_client *my_i2c_client;

// Probe function called when device is detected

static int my_i2c_probe(struct i2c_client *client, const struct i2c_device_id *id)

{

printk(KERN_INFO "I2C device detected at address 0x%02x\n", client->addr);

my_i2c_client = client;

return 0;

}

// Remove function called when driver is removed

static int my_i2c_remove(struct i2c_client *client)

{

printk(KERN_INFO "I2C device removed\n");

return 0;

}

// I2C device ID table

static const struct i2c_device_id my_i2c_id[] = {

{ DEVICE_NAME, 0 },

{ }

};

MODULE_DEVICE_TABLE(i2c, my_i2c_id);

// I2C driver structure

static struct i2c_driver my_i2c_driver = {

.driver = {

.name = DEVICE_NAME,

},

.probe = my_i2c_probe,

.remove = my_i2c_remove,

.id_table = my_i2c_id,

};

// Module init function

static int __init my_i2c_init(void)

{

int ret;

ret = i2c_add_driver(&my_i2c_driver);

if (ret)

printk(KERN_ERR "Failed to register I2C driver: %d\n", ret);

else

printk(KERN_INFO "I2C driver registered\n");

return ret;

}

// Module exit function

static void __exit my_i2c_exit(void)

{

i2c_del_driver(&my_i2c_driver);

printk(KERN_INFO "I2C driver unregistered\n");

}

module_init(my_i2c_init);

module_exit(my_i2c_exit);

MODULE_LICENSE("GPL");

MODULE_AUTHOR("Your Name");

MODULE_DESCRIPTION("Simple I2C Linux Driver Example");

What this driver does:

- Registers an I2C driver with the kernel.

- Detects a device at a given I2C address.

- Logs messages when the device is probed or removed.

Step 4: Write the Makefile

# Makefile for building the I2C driver

obj-m += i2c_driver.o

all:

make -C /lib/modules/$(shell uname -r)/build M=$(PWD) modules

clean:

make -C /lib/modules/$(shell uname -r)/build M=$(PWD) clean

Step 5: Compile the Driver

make

You should see i2c_driver.ko generated. This is the kernel module file.

Step 6: Load (Flash) the Driver

Load the module into the kernel:

sudo insmod i2c_driver.ko

Check kernel logs to see if it detected the I2C device:

dmesg | tail

Expected output:

I2C driver registered

I2C device detected at address 0x48

Step 7: Test the Driver

You can use i2c-tools to confirm device communication:

i2cdetect -y 1

To read/write data from the device:

# Read 1 byte from register 0x00

i2cget -y 1 0x48 0x00

# Write value 0x55 to register 0x01

i2cset -y 1 0x48 0x01 0x55

For more advanced testing, you can create a userspace program using /dev/i2c-X and the ioctl interface.

Step 8: Remove the Driver

sudo rmmod i2c_driver

dmesg | tail

Expected output:

I2C device removed

I2C driver unregistered

Step 9: Advanced Enhancements

Once the basic driver works, you can add:

- Read/Write operations in the driver using

i2c_smbus_read_byte_data()andi2c_smbus_write_byte_data(). - Interrupt handling for sensors.

- Device Tree integration for automatic binding on boot.

- Character device interface to allow userspace programs to communicate via

/dev/my_i2c_device.

Optional: Add Flash-Clear Functionality

If your device has flash memory, you can implement a flash clear function:

static void clear_device_flash(void)

{

int ret;

ret = i2c_smbus_write_byte_data(my_i2c_client, 0x00, 0x00); // Example

if (ret < 0)

printk(KERN_ERR "Failed to clear flash\n");

else

printk(KERN_INFO "Flash cleared successfully\n");

}

Call this in the probe function after device initialization if needed.

You can extend this driver by Implementing Interrupt handling and DMA support for faster data transfer .

Drivers in Linux: Interview Questions & Answers (I2C, SPI, GPIO)

If you’re preparing for an embedded Linux or kernel developer role, questions on drivers in Linux are very common. Below is a comprehensive list of interview questions along with human-friendly answers, covering both basics and advanced topics.

1. What are Drivers in Linux?

Answer:

Drivers in Linux are programs that allow the operating system to communicate with hardware devices. They act like a translator, converting generic OS commands into hardware-specific instructions. Without drivers, devices like keyboards, displays, or sensors cannot work properly with Linux.

2. What are the main types of Linux drivers?

Answer:

There are four main types:

- Character Device Drivers – Handle data as a stream (e.g., keyboard, serial ports).

- Block Device Drivers – Handle data in blocks (e.g., hard drives, SSDs).

- Network Device Drivers – Control network interfaces (Ethernet, Wi-Fi).

- Platform Drivers – Control on-board peripherals like I2C, SPI, GPIO devices.

3. What is an I2C driver in Linux?

Answer:

I2C (Inter-Integrated Circuit) is a two-wire communication protocol used to connect multiple peripherals with a master device.

In Linux, I2C drivers are divided into:

- I2C Adapter Driver: Handles the physical bus.

- I2C Client Driver: Handles the connected device, like a temperature sensor.

You can interact with I2C devices using i2cdetect and Linux APIs.

4. What is an SPI driver in Linux?

Answer:

SPI (Serial Peripheral Interface) is a faster, 4-wire protocol used for high-speed peripherals like ADCs or displays. Linux SPI drivers are divided into:

- SPI Master Drivers: Control the bus.

- SPI Device Drivers: Control the slave device.

SPI drivers use the Linux SPI subsystem APIs for reading, writing, and configuring devices.

5. What is a GPIO driver in Linux?

Answer:

GPIO (General Purpose Input/Output) allows control of simple hardware pins. GPIO drivers in Linux use the GPIO subsystem to read or write pin values.

For example, you can toggle an LED by writing 1 or 0 to a GPIO pin. Modern Linux exposes GPIO via /dev/gpiochipX (character device interface).

6. Difference between I2C and SPI?

Answer:

| Feature | I2C | SPI |

|---|---|---|

| Wires | 2 (SDA, SCL) | 4 (MISO, MOSI, SCLK, CS) |

| Speed | Slower | Faster |

| Devices | Multiple devices, shared bus | Multiple devices, separate CS lines |

| Use Case | Sensors, EEPROM | Displays, ADC/DAC, SD cards |

7. What is a Loadable Kernel Module (LKM)?

Answer:

An LKM is a driver that can be loaded or unloaded into the Linux kernel at runtime without rebooting.

- Commands:

insmod,rmmod,modprobe - Advantages: Modular, reduces kernel size, easy to update drivers.

8. How do you debug Linux drivers?

Answer:

Common tools include:

dmesg– Check kernel logslsmod– List loaded modulesstrace– Trace system callsgdborkgdb– Debug kernel code- Logging using

printk(KERN_INFO)inside the driver

9. How do interrupts work in Linux drivers?

Answer:

Interrupts notify the driver when a device needs attention instead of constantly polling.

- Saves CPU cycles

- Handled by IRQ handlers in the driver

- Common in GPIO (button press), SPI (data ready), I2C (sensor alert)

10. Can one driver handle multiple devices?

Answer:

Yes. For example:

- An I2C bus can have multiple sensors with unique addresses.

- SPI bus can have multiple devices using separate chip select (CS) pins.

FAQs on Drivers in Linux

1. What is the difference between I2C and SPI?

I2C uses 2 wires and is slower but simpler. SPI uses 4 wires, is faster, and supports higher data rates.

2. Can I write Linux drivers in Python?

No, Linux drivers must be written in C or C++ and compiled into the kernel. Python can interact with drivers via user-space APIs.

3. What is a loadable kernel module?

A module is a piece of code that can be loaded or removed from the kernel at runtime without rebooting.

4. How do I test a GPIO pin?

Use the sysfs interface or /dev/gpiochipX and toggle the pin value to see if connected hardware responds.

5. Are I2C addresses fixed?

No, most devices have configurable addresses, often set by hardware pins.

6. How do interrupts work in drivers?

Interrupts notify the driver when an event occurs, avoiding continuous polling and saving CPU resources.

7. Can a driver handle multiple devices?

Yes, modern drivers often support multiple clients or devices on the same bus.

8. Is kernel programming dangerous?

Mistakes can crash the system or corrupt memory. Always test in a virtual machine or development board.

9. How do I know if a driver is loaded?

Use lsmod to list modules and dmesg to check for kernel logs.

10. Can Linux drivers work across different boards?

Yes, but hardware-specific details like GPIO numbers or I2C bus IDs may need adjustment.

11. How to handle concurrency in drivers?

Use mutexes, spinlocks, or atomic operations provided by the kernel.

12. Do I need to reboot after loading a driver?

Not for loadable kernel modules. You can insert and remove modules without rebooting.

Conclusion

Mastering drivers in Linux opens the door to controlling and understanding hardware at a deep level. Whether you are dealing with I2C sensors, SPI displays, or GPIO pins, understanding how drivers work will empower you to build reliable and efficient systems. Start with simple character or GPIO drivers, then explore I2C and SPI devices, and gradually expand your knowledge to complex hardware subsystems.

Remember, writing drivers is a mix of learning kernel internals, understanding hardware, and practical coding. With patience and practice, you’ll be able to build your own embedded Linux projects with confidence.

Read More about Process : What is is Process

Read More about System Call in Linux : What is System call

Read More about IPC : What is IPC

Mr. Raj Kumar is a highly experienced Technical Content Engineer with 7 years of dedicated expertise in the intricate field of embedded systems. At Embedded Prep, Raj is at the forefront of creating and curating high-quality technical content designed to educate and empower aspiring and seasoned professionals in the embedded domain.

Throughout his career, Raj has honed a unique skill set that bridges the gap between deep technical understanding and effective communication. His work encompasses a wide range of educational materials, including in-depth tutorials, practical guides, course modules, and insightful articles focused on embedded hardware and software solutions. He possesses a strong grasp of embedded architectures, microcontrollers, real-time operating systems (RTOS), firmware development, and various communication protocols relevant to the embedded industry.

Raj is adept at collaborating closely with subject matter experts, engineers, and instructional designers to ensure the accuracy, completeness, and pedagogical effectiveness of the content. His meticulous attention to detail and commitment to clarity are instrumental in transforming complex embedded concepts into easily digestible and engaging learning experiences. At Embedded Prep, he plays a crucial role in building a robust knowledge base that helps learners master the complexities of embedded technologies.