Learn the Char Driver Model in Linux with a clear, beginner-friendly explanation. Understand structure, flow, key APIs, and real interview-focused concepts step by step.

The Char Driver Model is one of the most important building blocks in Linux device driver development. It defines how hardware devices that transfer data as a stream of bytes are exposed to user space and controlled through standard system calls. If you want to understand how Linux talks to real hardware, this is where the journey truly begins.

The article starts by clearly explaining what character drivers are and why they are widely used in Linux systems, especially in embedded, automotive, and custom hardware platforms. You will understand how synchronous drivers work, why blocking behavior exists, and how the kernel efficiently puts processes to sleep instead of wasting CPU cycles.

We then walk through driver registration and de-registration, explaining how major and minor numbers connect device files in /dev to the correct kernel driver. You will learn how Linux knows which driver should handle a read or write request and why proper cleanup during driver removal is critical for system stability.

The guide dives deep into the driver file interface, showing how character devices integrate with the Virtual File System. Each device file operation such as open, read, write, release, ioctl, poll, and mmap is explained in plain language with real-world meaning, not just definitions.

Special focus is given to driver data structures, helping you understand how drivers manage internal state, handle multiple devices, and support multiple processes safely. You will also learn how device configuration operations using ioctl allow flexible control of hardware without breaking user space compatibility.

Advanced but essential topics like wait queues and polling are covered with clarity, explaining how Linux handles blocking and non-blocking I/O, event-driven applications, and efficient synchronization. The section on memory mapping explains how high-performance drivers avoid unnecessary data copying and safely expose device memory to user space.

To prepare you for real-world interviews, the guide also aligns closely with Round 1 and Round 2 interview expectations, helping you understand not just what the Char Driver Model is, but how and why it is designed this way.

By the end of this article, you will have a strong, practical understanding of the Char Driver Model, making you confident in Linux driver interviews, embedded system projects, and kernel-level development work.

Introduction: Why the Char Driver Model Still Matters

If you are learning Linux device drivers, the Char Driver Model is not optional knowledge. It is the foundation. Almost every serious kernel developer starts here, because character drivers teach you how the kernel and user space talk to each other.

Whether you are working on:

- Embedded Linux

- Automotive platforms

- BSP development

- Custom hardware bring-up

You will meet character drivers early and often.

A char driver handles devices that:

- Transfer data as a stream of bytes

- Do not use fixed block sizes

- Often require synchronous or event-driven access

Examples include:

- Serial ports

- GPIO drivers

- I2C and SPI devices

- Sensors

- Custom hardware peripherals

Understanding the Char Driver Model means understanding how Linux exposes hardware safely, cleanly, and efficiently to user space.

What Is the Char Driver Model?

At its core, the Char Driver Model defines how a character device is:

- Registered with the kernel

- Exposed to user space as a device file

- Accessed using standard system calls like

open,read,write, andioctl

Unlike block drivers (used for disks) or network drivers (used for packets), a char driver:

- Reads and writes bytes

- Works sequentially

- Often operates synchronously

This makes char drivers simpler to understand and perfect for learning Linux driver architecture.

Synchronous Drivers Defined

Let’s clarify something early because this topic confuses beginners.

What does “synchronous driver” mean?

A synchronous driver blocks the calling process until an operation completes.

Example:

- A user calls

read() - The driver waits until data is available

- The process sleeps

- Data arrives

- The process wakes up

read()returns

This behavior is extremely common in char drivers.

Why synchronous behavior matters

Synchronous drivers:

- Are easier to reason about

- Avoid race conditions when designed correctly

- Match how real hardware behaves

Linux also supports non-blocking and asynchronous I/O, but the Char Driver Model is built around synchronous behavior first, then extended using:

- Wait queues

- Polling

- Select

- Async notifications

We will cover those later.

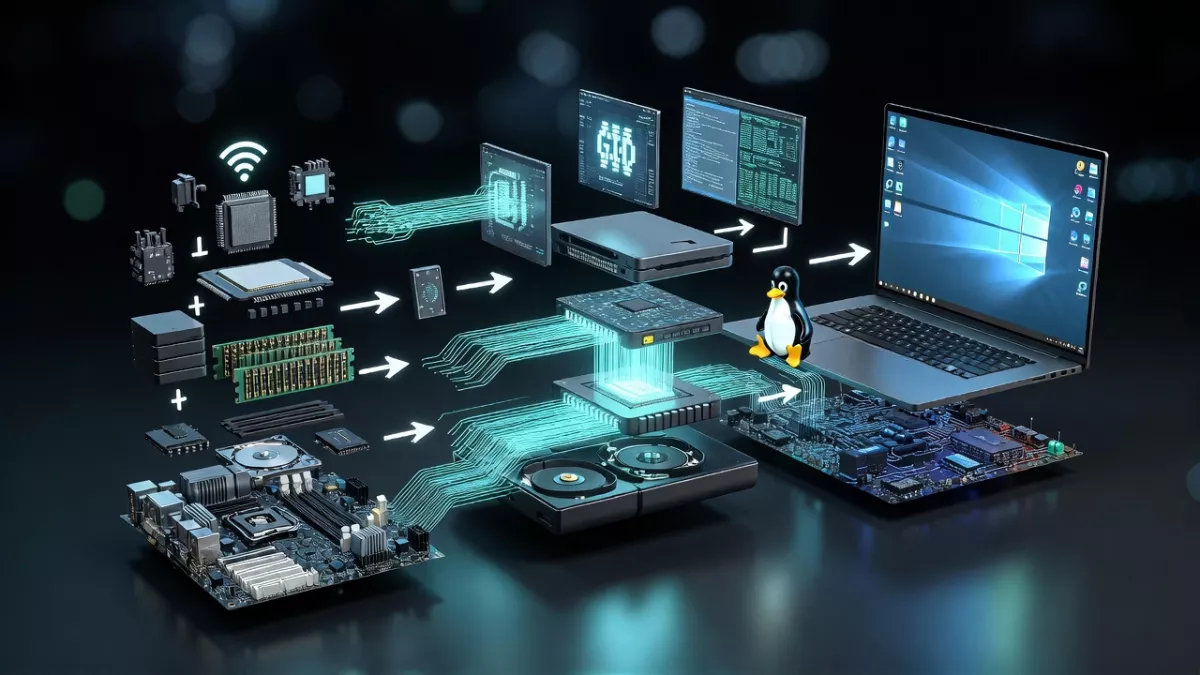

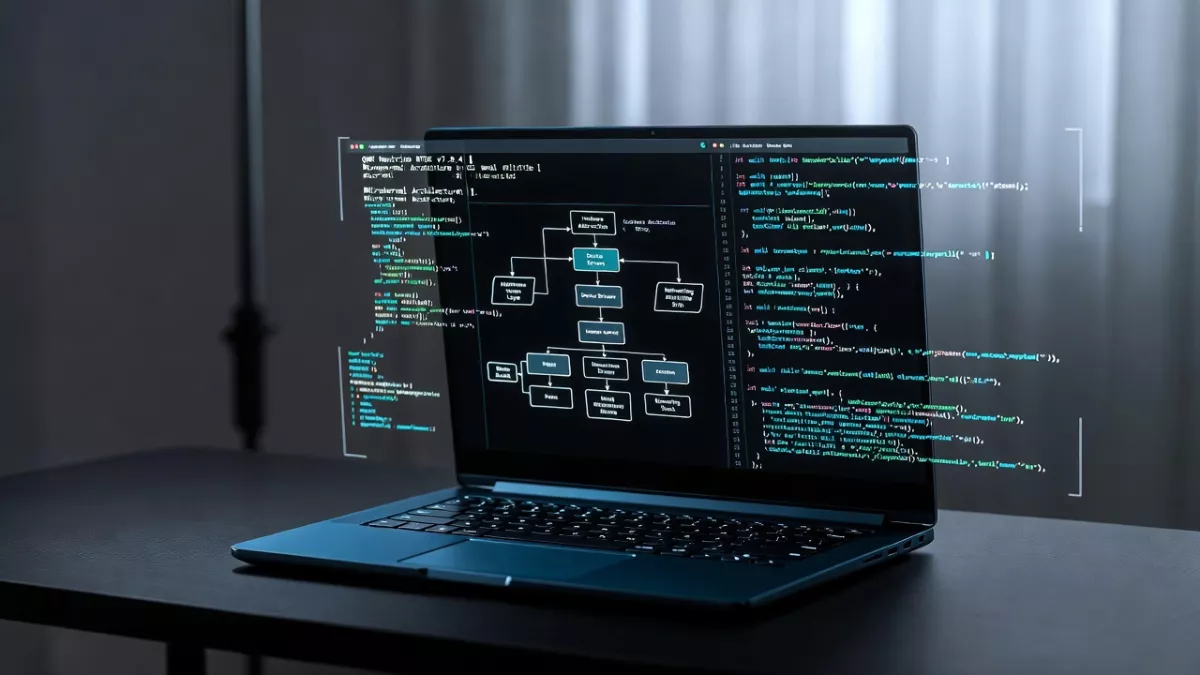

Char Driver Model Architecture Overview

Let’s zoom out and look at the big picture.

User space talks to a char driver through:

/devdevice files- Standard POSIX system calls

The kernel connects everything using:

- Major and minor numbers

- File operations

- Internal driver data structures

The flow looks like this:

- Application opens

/dev/mydevice - Kernel maps it to a registered char driver

- Kernel calls driver callbacks

- Driver talks to hardware

- Data flows back to user space

Simple concept. Powerful mechanism.

Driver Registration and De-registration

This is where every char driver begins and ends.

Why registration exists

Linux needs to know:

- Which driver owns which device

- How to route file operations to the correct code

This is done through driver registration.

Registering a Char Driver

The kernel identifies char drivers using:

- Major number: identifies the driver

- Minor number: identifies devices handled by that driver

There are two common approaches:

Static major number

You pick a number yourself (not recommended anymore).

Dynamic major number

The kernel assigns one for you.

Modern drivers always use dynamic registration.

Typical steps:

- Allocate device numbers

- Initialize character device structure

- Add the device to the kernel

This is where the Char Driver Model starts to feel real.

Driver De-registration

When a driver is removed:

- Device numbers must be freed

- Kernel objects must be cleaned

- Memory must be released

Failing to de-register properly leads to:

- Kernel crashes

- Memory leaks

- Broken

/devnodes

Clean de-registration is a sign of a professional driver.

Driver File Interface

The driver file interface is how Linux makes your hardware look like a file.

That is not a metaphor. It is literal.

Everything in Linux is a file, including:

- Sensors

- LEDs

- UARTs

- Custom ASICs

The Char Driver Model plugs into the VFS (Virtual File System) layer.

The Role of /dev

When you create a device file like:

/dev/my_char_device

Linux connects:

- User space file operations

- To your driver callbacks

That connection happens through the file operations structure.

Device File Operations

This is the heart of the Char Driver Model.

What are device file operations?

They are function pointers that define how your driver responds to:

open()read()write()close()ioctl()poll()mmap()

When a user calls read(), the kernel does not read hardware itself.

It calls your function.

Common file operations explained

open

Called when a process opens the device file.

Used to:

- Initialize private data

- Allocate resources

- Check permissions

read

Transfers data from kernel space to user space.

Key responsibilities:

- Copy data safely

- Handle blocking behavior

- Respect file position

write

Transfers data from user space to kernel space.

Used for:

- Sending commands

- Writing configuration

- Controlling hardware behavior

release (close)

Called when the file descriptor is closed.

Used to:

- Free resources

- Decrement usage counters

ioctl: Device configuration ops

This deserves its own section.

Device Configuration Ops (ioctl)

Not all device control fits into read and write.

That is why device configuration ops exist.

The ioctl() system call allows:

- Sending control commands

- Passing structured data

- Changing device modes

Examples:

- Set baud rate

- Enable interrupts

- Switch operating modes

- Query device status

In the Char Driver Model, ioctl is how drivers stay flexible without breaking APIs.

Why ioctl must be designed carefully

Bad ioctl design causes:

- ABI breakage

- Security issues

- Maintenance nightmares

Good ioctl design:

- Uses versioned commands

- Validates input

- Copies data safely

Driver Data Structures

Behind every clean driver is a solid data model.

Why driver data structures matter

Drivers need to store:

- Device state

- Hardware configuration

- Buffers

- Synchronization primitives

This data must:

- Be private to the driver

- Be safe in concurrent access

- Scale across multiple devices

Common driver data structures

Most char drivers use:

- A per-device structure

- A pointer stored in

file->private_data

This allows:

- Multiple processes

- Multiple devices

- Clean separation of state

Good data structure design makes the rest of the driver simpler.

Wait Queues and Polling

Now we get into real-world behavior.

Why wait queues exist

Hardware is slow. CPUs are fast.

Instead of busy-waiting, Linux uses wait queues.

When a process needs data:

- It sleeps

- The driver puts it on a wait queue

- Hardware interrupt occurs

- Driver wakes the process

This is efficient and scalable.

Blocking vs non-blocking I/O

Blocking:

read()waits until data is ready

Non-blocking:

read()returns immediately- Application retries later

The Char Driver Model supports both.

Polling and select

Applications often want to wait on:

- Multiple devices

- Timers

- Sockets

The poll() and select() interfaces allow this.

Your driver must:

- Implement a poll callback

- Report readiness correctly

This is essential for:

- Event-driven applications

- GUI programs

- Embedded control loops

Memory Mapping

This is where char drivers become powerful.

What is memory mapping?

Memory mapping allows:

- User space to access device memory directly

- Zero-copy data transfer

- High performance I/O

Instead of copying data, the kernel maps memory into user space.

When memory mapping is useful

Common use cases:

- Frame buffers

- ADC buffers

- DMA memory

- High-speed sensors

The Char Driver Model supports memory mapping using mmap().

Safety considerations

Memory mapping must:

- Restrict access properly

- Prevent kernel memory leaks

- Validate ranges

Done correctly, it is fast and safe.

Done poorly, it crashes systems.

How All Pieces Fit Together

Let’s connect everything.

A typical char driver:

- Registers itself with the kernel

- Creates a device file

- Implements file operations

- Manages driver data structures

- Handles synchronous access

- Uses wait queues for blocking I/O

- Supports polling for event-driven apps

- Exposes configuration via ioctl

- Optionally supports memory mapping

This is the Char Driver Model in action.

Common Mistakes Beginners Make

Let’s be honest.

Most first drivers fail because of:

- Poor synchronization

- Missing error handling

- Incorrect user memory access

- Forgetting de-registration

- Unsafe ioctl implementations

Avoiding these mistakes puts you ahead of 80 percent of beginners.

Why the Char Driver Model Is Still Relevant in 2026

Despite newer frameworks:

- Char drivers remain the backbone

- Many subsystems still rely on them

- Embedded Linux depends heavily on char devices

If you want to:

- Write custom drivers

- Understand kernel internals

- Debug low-level issues

You must master the Char Driver Model.

Char Driver Model Interview Questions and Answers

ROUND 1: Basics & Conceptual Questions

1. What is a character driver in Linux?

A character driver is a Linux device driver that transfers data as a stream of bytes. It does not use fixed-size blocks like disk drivers. User space interacts with it using standard system calls like open, read, write, and ioctl through a device file in /dev.

2. What is the Char Driver Model?

The Char Driver Model defines how a character device is registered with the kernel, how it is exposed to user space, and how file operations from applications are handled inside the driver.

3. What are some real examples of character devices?

Serial ports, GPIO drivers, I2C devices, SPI devices, sensors, LEDs, RTCs, and many embedded peripherals are implemented as character drivers.

4. What is meant by synchronous drivers?

Synchronous drivers block the calling process until the requested operation completes. For example, a read call waits until data is available instead of returning immediately.

5. What is a device file?

A device file is a special file created in /dev that represents a hardware device. It acts as the connection point between user space and the kernel driver.

6. What is a major number?

The major number identifies the driver in the kernel. When a device file is accessed, the kernel uses the major number to find which driver should handle the request.

7. What is a minor number?

The minor number identifies a specific device instance handled by the same driver. One driver can manage multiple devices using different minor numbers.

8. How does user space talk to a char driver?

Through system calls like open, read, write, close, ioctl, poll, and mmap on the device file.

9. What is driver registration?

Driver registration is the process where a character driver informs the kernel about its existence, the device numbers it handles, and the file operations it supports.

10. Why is driver de-registration important?

If a driver is not properly de-registered, it can leave dangling references, memory leaks, or crash the kernel when the module is removed.

11. What is the file operations structure?

It is a structure that contains function pointers to driver callbacks like open, read, write, release, ioctl, poll, and mmap. The kernel calls these functions when user space performs file operations.

12. What happens when an application calls read()?

The kernel calls the driver’s read callback, and the driver copies data from kernel space to user space, possibly blocking until data is available.

13. What is ioctl used for?

Ioctl is used for device-specific control operations that do not fit into read or write, such as configuring hardware settings or querying device status.

14. Can multiple processes access a char device?

Yes, multiple processes can access a char device unless the driver explicitly restricts access using synchronization or open logic.

15. What is blocking I/O?

Blocking I/O means the calling process sleeps until the requested operation can be completed, such as waiting for data from hardware.

ROUND 2: Deep-Dive & Scenario-Based Questions

16. How does the kernel know which driver handles a device file?

When a device file is opened, the kernel checks its major number and routes the request to the registered char driver associated with that major number.

17. What happens internally when open() is called?

The kernel creates a file structure, links it to the inode, and then calls the driver’s open callback, allowing the driver to initialize device-specific data.

18. Why do drivers use file->private_data?

It allows the driver to store per-open or per-device data so that each process has its own context when accessing the device.

19. What are driver data structures?

They are internal structures used by the driver to store device state, buffers, configuration, synchronization objects, and hardware-specific information.

20. How does a driver handle concurrent access?

Using synchronization mechanisms like mutexes, spinlocks, atomic variables, and wait queues to protect shared data.

21. What are wait queues?

Wait queues allow processes to sleep until a specific condition occurs, such as data becoming available or a hardware interrupt firing.

22. Why are wait queues better than busy waiting?

Busy waiting wastes CPU cycles. Wait queues put the process to sleep and wake it only when needed, making the system efficient.

23. How does a driver wake up sleeping processes?

Usually from an interrupt handler or workqueue using wake-up functions associated with the wait queue.

24. What is polling in char drivers?

Polling allows applications to check whether a device is ready for read or write without blocking, commonly used with select or poll system calls.

25. When should poll() be implemented?

When your device generates events or data asynchronously and applications need to monitor readiness along with other file descriptors.

26. What is non-blocking I/O?

Non-blocking I/O returns immediately if data is not available, instead of putting the process to sleep.

27. How does a driver support non-blocking read?

By checking the file flags and returning an error code instead of sleeping if data is not ready.

28. What is memory mapping in char drivers?

Memory mapping allows a driver to map kernel or device memory directly into user space so applications can access it without copying.

29. Why is mmap useful?

It improves performance for large data transfers like video frames, DMA buffers, or continuous sensor data.

30. What are risks of memory mapping?

If not handled carefully, it can expose kernel memory, cause security issues, or crash the system.

31. What is the role of ioctl in device configuration ops?

Ioctl allows structured control commands to configure hardware settings that cannot be represented as simple read or write operations.

32. How do you design safe ioctl commands?

By validating inputs, checking user memory, using versioned commands, and maintaining backward compatibility.

33. What happens if a driver forgets to free resources on exit?

It can cause memory leaks, dangling device nodes, or kernel panics when the module is unloaded.

34. How does the Char Driver Model support multiple devices?

By using multiple minor numbers and separate device data structures for each instance.

35. Why is error handling important in char drivers?

Because a mistake can crash the entire kernel, not just one application.

36. What debugging methods are used for char drivers?

Kernel logs, printk, dynamic debug, ftrace, crash dumps, and careful code review.

37. What is the difference between char and block drivers?

Char drivers work with byte streams and sequential access, while block drivers work with fixed-size blocks and random access.

38. Is Char Driver Model still relevant today?

Yes. It is widely used in embedded systems, automotive platforms, and custom hardware even in modern Linux kernels.

39. What does an interviewer expect from a char driver engineer?

Clear understanding of kernel-user interaction, synchronization, clean resource management, and safe hardware access.

40. How do you explain Char Driver Model in one line?

It is the Linux framework that lets hardware behave like a file so applications can interact with it safely and efficiently.

Final Thoughts

The Char Driver Model is not just a learning step.

It is a professional skill.

Once you understand:

- Synchronous drivers

- Driver registration and de-registration

- Driver file interface

- Device file operations

- Driver data structures

- Device configuration ops

- Wait queues and polling

- Memory mapping

You are no longer “learning drivers.”

You are writing real Linux drivers.

FAQ : Char Driver Model in Linux

1. What is the Char Driver Model in Linux?

The Char Driver Model is a Linux kernel framework used to handle character devices that transfer data one byte at a time, such as keyboards, sensors, serial ports, and GPIO-based devices.

2. Why is a character driver called a “char” driver?

It is called a char driver because it handles data as a stream of characters (bytes) rather than fixed-size blocks like block drivers.

3. Where is the Char Driver Model used in real systems?

Char drivers are used in UART devices, I2C sensors, GPIO interfaces, RTCs, touch controllers, and many embedded and automotive Linux systems.

4. What are the main components of the Char Driver Model?

The core components are:

- Major and minor numbers

file_operationsstructure- Device file in

/dev - Kernel module initialization and cleanup functions

5. What is a major and minor number in a char driver?

The major number identifies the driver, while the minor number identifies individual devices handled by the same driver.

6. What is the role of file_operations in a char driver?

file_operations links user-space system calls like open(), read(), and write() to kernel-space driver functions.

7. How does user space communicate with a char driver?

User space communicates through system calls using a device file created in /dev, such as /dev/mydevice.

8. What is register_chrdev() used for?

register_chrdev() is used to register a character driver with the kernel and assign it a major number.

9. What is cdev and why is it important?

cdev is a kernel structure that represents a character device and connects it to the VFS layer for proper device handling.

10. How is a device file created for a char driver?

A device file can be created manually using mknod or automatically using udev with class_create() and device_create().

11. What is the difference between char driver and block driver?

Char drivers handle data byte-by-byte, while block drivers manage fixed-size blocks and support random access, such as hard disks.

12. What happens when open() is called on a char device?

The kernel invokes the driver’s open() callback, allowing the driver to initialize hardware or allocate resources.

13. What is ioctl() in the Char Driver Model?

ioctl() allows custom control commands from user space to the driver, commonly used for configuration and device control.

14. Are char drivers used in embedded Linux?

Yes, char drivers are heavily used in embedded Linux for sensors, communication interfaces, and hardware control.

15. Is learning the Char Driver Model important for interviews?

Yes, it is a core Linux driver topic and is frequently asked in embedded Linux and kernel developer interviews.

Read More about Process : What is is Process

Read More about System Call in Linux : What is System call

Read More about IPC : What is IPC

Mr. Raj Kumar is a highly experienced Technical Content Engineer with 7 years of dedicated expertise in the intricate field of embedded systems. At Embedded Prep, Raj is at the forefront of creating and curating high-quality technical content designed to educate and empower aspiring and seasoned professionals in the embedded domain.

Throughout his career, Raj has honed a unique skill set that bridges the gap between deep technical understanding and effective communication. His work encompasses a wide range of educational materials, including in-depth tutorials, practical guides, course modules, and insightful articles focused on embedded hardware and software solutions. He possesses a strong grasp of embedded architectures, microcontrollers, real-time operating systems (RTOS), firmware development, and various communication protocols relevant to the embedded industry.

Raj is adept at collaborating closely with subject matter experts, engineers, and instructional designers to ensure the accuracy, completeness, and pedagogical effectiveness of the content. His meticulous attention to detail and commitment to clarity are instrumental in transforming complex embedded concepts into easily digestible and engaging learning experiences. At Embedded Prep, he plays a crucial role in building a robust knowledge base that helps learners master the complexities of embedded technologies.