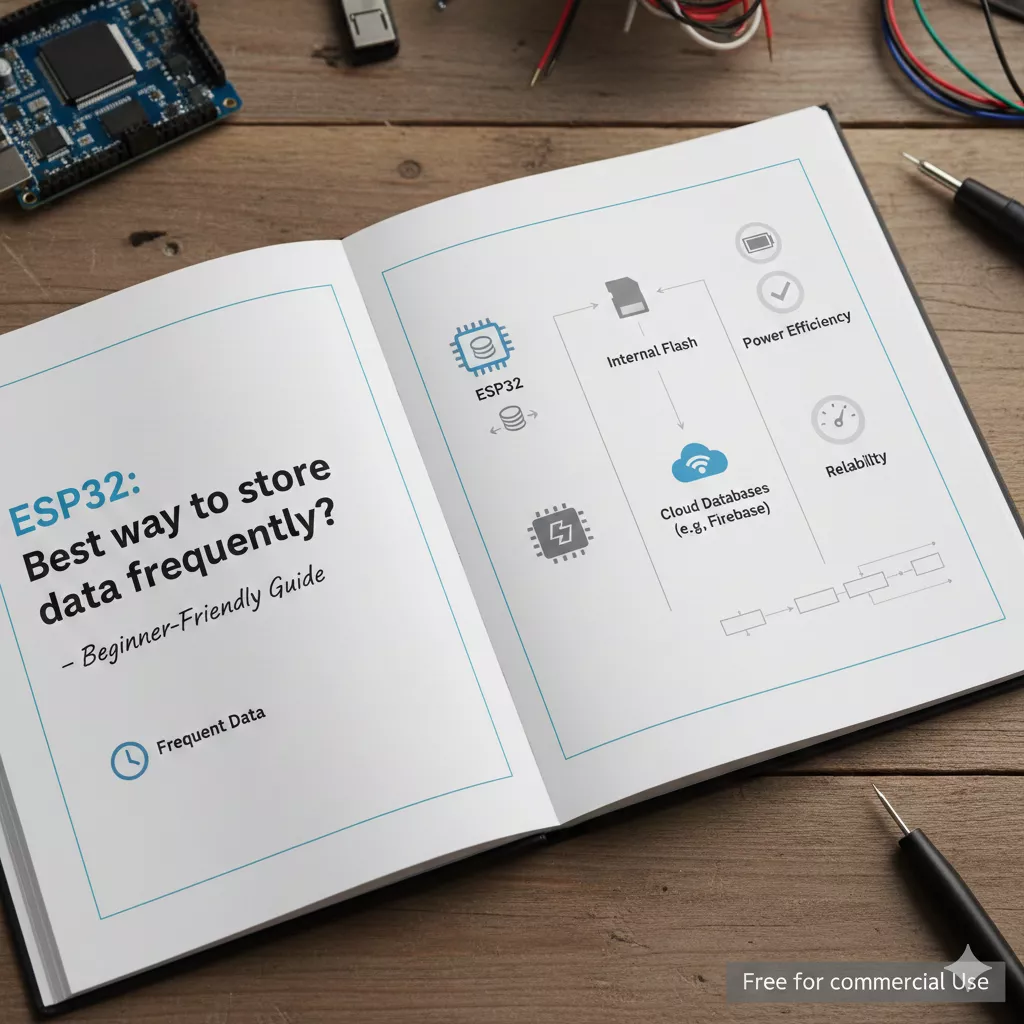

Discover ESP32: Best way to store data frequently? Learn how to store data in RAM, EEPROM, SPIFFS, NVS, SD card, and FRAM for efficient persistent logging.

So, you’ve got an ESP32 board humming away, collecting sensor readings or user inputs, and you want to store data frequently maybe every second, maybe every minute — without losing anything when the power goes off. Choosing how to store data on the ESP32 is more than just picking between RAM and flash: it’s about durability, speed, memory capacity, and wear. In this guide, I’ll walk you through ESP32: Best way to store data frequently, reviewing key storage options, trade‑offs, and practical tips. By the end, you’ll know exactly how to pick and implement a storage strategy for your project.

Why Data Storage Matters for ESP32 Projects

In many embedded projects especially with ESP32 you need persistent data storage: you don’t just want to hold data in memory (RAM) for a moment, you want to keep it around between reboots, or log it over time.

- If you’re building a data logger, you’ll want to store sensor readings to analyze trends later.

- If your system should recover gracefully after a power cut, you need persistent storage.

- Frequently saving data helps prevent loss when something goes wrong.

But “frequently” adds complexity. Writing too often to certain types of storage wears them out fast. So, let’s break down the options.

Overview of ESP32 Storage Options

Here are the main storage mechanisms you can use on an ESP32, along with their trade-offs:

- RAM (volatile memory)

- EEPROM (emulated)

- SPIFFS or LittleFS (filesystem in flash)

- Non-volatile storage (NVS)

- SD card storage

- External flash or FRAM

- RTC memory

Let’s examine each in detail.

1. ESP32 Store Data in RAM

What is RAM storage?

Running variables on the ESP32 use RAM. This is super fast, easy to use, but volatile once the power goes, all data is gone.

Use-cases and limitations

- Good for: temporary data, caching, computations, real-time buffers.

- Bad for: anything that must survive a reset or power cycle.

If you store data only in RAM, you risk losing everything when you reset or lose power. That’s fine if you’re just handling live data, but not for persistent logging.

2. ESP32 Store Data in EEPROM (Emulated)

What is EEPROM on ESP32?

The ESP32 doesn’t have real EEPROM, but you can emulate EEPROM using a portion of flash memory. Using the Arduino-ESP32 core, for instance, you get an EEPROM library that reserves flash pages.

Pros and cons

- Pros: Simple API, good for storing small, fixed-size variables (like calibration data or counters).

- Cons: Limited write cycles per flash page (~10,000–100,000), slow relative to RAM, and you need to manage page boundaries yourself.

When to use EEPROM-style storage

Keeping persistent counters, configuration values, or a few small flags. When data size is small and structure is fixed, you can combine EEPROM-style storage with other ESP32 solutions for advanced projects. For example, check out the ESP32-C6 PoE development board for projects that need reliable connectivity and storage options.

3. ESP32 Store Data in Flash via File System (SPIFFS / LittleFS)

What is SPIFFS / LittleFS?

These are filesystems that run inside the flash on the ESP32. You can treat part of your flash partition like disk storage: open files, write, read, and delete.

Pros

- Good for persistent storage of log files, JSON, or chunks of data.

- Supports large data (relative to EEPROM), depending on how big your partition is.

- Easier to manage structured data (files, folders).

Cons

- Flash wear: every write-erases and rewrites entire blocks; you need to minimize writes.

- File system overhead.

- Less endurance for frequent writes compared to more specialized storage.

Use-case for frequent data logging

If you’re logging data (e.g., sensor telemetry) and can buffer writes, using SPIFFS or LittleFS is often a solid choice. You might accumulate data in RAM and flush to SPIFFS periodically rather than writing every second.

4. ESP32 Non-Volatile Storage (NVS)

What is NVS?

NVS is a key-value storage system built into ESP-IDF (the underlying framework for ESP32). It stores data in flash in a way optimized for small writes and wear leveling.

Pros

- Better wear leveling than raw flash.

- Optimized for frequent writes of small pieces of data.

- Offers a simple API for storing integers, strings, blobs, etc.

Cons

- Not designed for huge blobs (very large logs).

- Limited by partition size.

When to use NVS

- Configuration, calibration, or small but critical data.

- Frequent updates of small variables.

- When you don’t need a full file system.

5. ESP32 Store Data on SD Card

What is SD card storage?

You can connect an SD card to the ESP32 via SPI or SDIO. Then you mount a FAT or similar filesystem and read/write files like a microcontroller with an SD card.

Pros

- Huge capacity: gigabytes of space, perfect for large logs.

- Write cycles are not a major concern: SD cards are durable for logging.

- Filesystem familiar (FAT, exFAT) and easy to manage.

Cons

- Requires more hardware (SD card slot or module).

- Slightly more complex code to mount, read, write.

- Power consumption; you might need to handle unmounting cleanly to avoid corruption.

Use-case for frequent logging

If you’re doing long-term data logging — say recording sensor data every second for days or weeks SD card is likely the best. It gives you persistent storage, room to store large data, and is cost-effective.

6. External Flash or FRAM

What is external flash / FRAM?

You can attach a secondary flash chip or FRAM (ferroelectric RAM) to the ESP32 via SPI or QSPI. FRAM is particularly excellent for frequent writes because it supports virtually unlimited write cycles.

Pros

- FRAM: extremely high endurance, good for writing often.

- External storage: more capacity, more flexibility.

- Can implement circular buffers, ring logs, or journaling easily.

Cons

- More hardware complexity.

- Slightly more power consumption.

- Need to write your own driver / data management.

When to pick external memory

- Applications needing very frequent writes (like real-time data logging).

- Projects where you can afford extra cost / hardware.

- When flash endurance is a concern, or you need large persistent storage.

7. ESP32 Store Data in RTC Memory

What is RTC memory?

The ESP32 has a small region of RTC (Real-Time Clock) memory, which stays powered in certain sleep modes (if configured). Useful for caching small data across deep sleeps.

Pros

- Low latency, small storage.

- Good for saving a few variables across deep sleep cycles.

- Doesn’t wear out like flash.

Cons

- Very limited in size.

- Not persistent forever—loses data if power is fully removed.

When to use RTC memory

- Storing wake reason, last sample, or counters across sleep/wake cycles.

- Not for bulk logging, but great for maintaining context.

So, What’s the Best Approach ESP32: Best Way to Store Data Frequently?

Now, based on what you’ve learned, how do you pick the best way to store data frequently on ESP32? There’s no one-size-fits-all — it depends on your use-case. Here are some rules of thumb, and a few recommended strategies.

Key Factors to Consider

- Write Frequency: How often are you writing?

- Data Size: How much data per write?

- Persistence: Does the data need to survive power loss?

- Memory Capacity: How much storage do you need?

- Hardware Constraints: Do you have an SD card slot, or only internal flash?

- Endurance Requirements: How important is flash wear?

- Power Constraints: Are deep sleeps involved?

Strategy 1: NVS for Small, Frequent Writes

If your data is small (like integers, counters, or short strings), and you need to update it frequently, then NVS is often the best choice.

- Use NVS to store key-value pairs.

- Every write goes through wear-leveling, so flash doesn’t wear quickly.

- Because it’s integrated with ESP-IDF, it’s fairly straightforward.

Example:

#include "nvs_flash.h"

#include "nvs.h"

void init_storage() {

esp_err_t err = nvs_flash_init();

if (err == ESP_ERR_NVS_NO_FREE_PAGES ||

err == ESP_ERR_NVS_NEW_VERSION_FOUND) {

// NVS partition was truncated, erase and retry

ESP_ERROR_CHECK(nvs_flash_erase());

ESP_ERROR_CHECK(nvs_flash_init());

}

ESP_ERROR_CHECK(err);

}

void store_counter(int32_t count) {

nvs_handle_t my_handle;

ESP_ERROR_CHECK(nvs_open("storage", NVS_READWRITE, &my_handle));

ESP_ERROR_CHECK(nvs_set_i32(my_handle, "counter", count));

ESP_ERROR_CHECK(nvs_commit(my_handle));

nvs_close(my_handle);

}

int32_t load_counter() {

nvs_handle_t my_handle;

int32_t count = 0;

ESP_ERROR_CHECK(nvs_open("storage", NVS_READONLY, &my_handle));

ESP_ERROR_CHECK(nvs_get_i32(my_handle, "counter", &count));

nvs_close(my_handle);

return count;

}

This is great when you periodically update a small number and can afford the slight latency of commit.

Strategy 2: SPIFFS / LittleFS for Log Files

If your data is larger or structured, such as JSON or CSV logs, use SPIFFS or LittleFS.

How to do it well:

- Buffer in RAM: Accumulate data in a buffer in RAM.

- Flush periodically: Write to the file system only every few seconds or minutes.

- Rolling logs: Use a ring-buffer approach—once file is large enough, rotate or archive.

- Minimize writes: Combine many entries into one write to reduce write cycles.

Example (Arduino-style):

#include "SPIFFS.h"

void setup() {

SPIFFS.begin(true);

}

void logData(String entry) {

static File logFile = SPIFFS.open("/datalog.csv", FILE_APPEND);

if (!logFile) {

Serial.println("Failed to open log file");

return;

}

logFile.println(entry);

logFile.flush(); // ensures data is written

}

void loop() {

String data = String(millis()) + "," + String(analogRead(34));

logData(data);

delay(1000); // log every second

}

This is good when you want a persistent file that you can read later by mounting SPIFFS or extracting the flash contents.

Strategy 3: SD Card for High-Volume Logging

If you’re collecting a lot of data — maybe high-frequency sensor data, or you want to keep data for days — use SD card storage.

Best practice:

- Use the SD library or

SD_MMC(if using SDIO). - Create a file (or files) on FAT filesystem.

- Write in batches, not every sample individually if you can help it.

- Handle clean dismount: ensure you properly close files before power-off.

Example (Arduino-style):

#include "SD.h"

#define SD_CS_PIN 5

void setup() {

if (!SD.begin(SD_CS_PIN)) {

Serial.println("SD init failed");

return;

}

}

void logToSD(String entry) {

File file = SD.open("/log.txt", FILE_APPEND);

if (!file) {

Serial.println("Failed to open file");

return;

}

file.println(entry);

file.close();

}

void loop() {

uint64_t timestamp = esp_timer_get_time(); // get microseconds since boot

String entry = String(timestamp) + "," + String(analogRead(34));

logToSD(entry);

delay(1000);

}

This is ideal when space is a concern and you want serious persistence.

Strategy 4: External Flash or FRAM for High Endurance

If your application demands hundreds of thousands or millions of writes, internal flash might wear out too soon. In that case, external FRAM or external flash is your friend.

How to do it:

- Use SPI to connect to a FRAM chip.

- Implement a circular buffer (ring log).

- Use a header/footer for each record (timestamp, length, CRC) to recover after power loss.

Pros:

- FRAM supports very high number of writes.

- You can maintain continuous logging with minimal wear worry.

Cons:

- Hardware complexity.

- You need to write or adapt a wear-leveling or journaling mechanism.

Strategy 5: Using RTC Memory for Sleep-Wake Persistence

If your ESP32 uses deep sleep, you might want to save a few bytes across sleep cycles. The RTC memory is perfect for that.

Typical usage:

- Store a last sample, counter, or a wake-up reason.

- Recover state quickly after wake.

Code snippet (ESP-IDF):

RTC_DATA_ATTR int bootCount = 0;

void app_main() {

bootCount++;

printf("Boot count: %d\n", bootCount);

esp_deep_sleep(1000000); // sleep for 1 second

}

This data is fast to access, and you don’t wear out flash for trivial counters or state management.

Implementing a Reliable Data Logger Putting It All Together

Let’s combine some of these strategies into a reliable data logger, using an ESP32 collecting sensor data, timestamped, stored frequently, and surviving resets.

Step 1: Get System Time ESP32 Get System Time

You’ll want meaningful timestamps. Use esp_timer_get_time() (ESP-IDF) to get microseconds since boot, or sync with an RTC/NTP if you need real-world timestamps.

int64_t now_us = esp_timer_get_time(); // microseconds since boot

time_t now_s = time(NULL); // if you’ve set up NTP

Using real-world time is better for logs, but boot-relative time is faster and simpler.

Step 2: Buffering Strategy

- In your loop, collect data every second.

- Append data to a RAM ring buffer (an array or vector).

- Every N samples (say, 10), flush to storage (SPIFFS, SD, or FRAM).

This reduces write frequency and extends lifetime if writing to flash.

Step 3: Choosing Storage

- Use NVS for small state (e.g., last write pointer, metadata).

- Use SPIFFS or LittleFS or SD card for logs.

- If you have FRAM, use it for a high-cycle journal.

Step 4: Error Handling and Recovery

- On startup, open your log store.

- If corrupted file or partition, handle gracefully (rename or recreate).

- Use CRC or checksums per record if data integrity matters.

- Commit NVS after writing pointer updates.

Comparing the Options: Trade-offs at a Glance

| Storage Option | Endurance (writes) | Capacity | Speed | Complexity | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAM | Unlimited (volatile) | Small | Fast | Very simple | Temporary buffering |

| EEPROM (emulated) | ~10k–100k | Small | Medium | Simple API | Config / counters |

| NVS | Better wear-leveling | Small to medium | Medium | Moderate | Key-value state |

| SPIFFS / LittleFS | Moderate | Medium | Slow‑medium | Moderate | Log files, structured data |

| SD Card | Very high (for log use) | Very large | Medium | Hardware + software | High-volume data logging |

| External FRAM | Very high (millions) | Medium | Fast | Hardware + software | Frequent writes, wear-sensitive logging |

| RTC Memory | Unlimited (in sleep) | Very small | Fast | Very simple | Sleep persistence, counters |

Best Practices for Frequent Storage on ESP32

Here are some tips to make sure your data logging is reliable, efficient, and safe:

- Minimize writes to flash

Buffer data in RAM, then write in batches. - Use wear leveling

Use NVS or journaling to spread out writes evenly. - Use checksums / CRC

When logging critical data, store a CRC or checksum to validate integrity on read. - Close and flush files

When using SPIFFS or SD, flush data and close files properly so you don’t corrupt them on power loss. - Use partitioning

In ESP-IDF, create separate partitions for NVS, filesystem, and application so you don’t run out of space or interfere. - Optimize for power

If you’re using deep sleep, combine RTC memory with infrequent flash writes. - Recovery strategy

On startup, detect if log was corrupted, and handle it (rename old logs, restart log). - Monitor wear

If you’re using flash heavily, track how many writes you’re doing; use external memory (FRAM) if needed. - Time management

Useesp_timer_get_time()or NTP to timestamp data cleanly. - Design logs carefully

Choose a log format (binary, JSON, CSV) that balances parseability and space.

Example Project: ESP32 Data Logger

Imagine you’re building a temperature logger with an ESP32, a DHT22 sensor, and you want to log temperature every 10 seconds, timestamped, storing logs for days.

Here’s a high-level design:

- Use NTP (Network Time Protocol) to sync time at startup.

- Fetch temperature every 10 seconds.

- Append data (timestamp + temperature) to a RAM buffer (maybe a

std::vector<String>or C array). - Every minute (6 samples), write the buffer to SPIFFS as a CSV file.

- In NVS, record how many lines you have written and your file pointer.

- On reboot, open the existing log file and resume appending.

- Use a rolling scheme: when the file surpasses, say, 1 MB, start a new file (e.g.,

log_001.csv,log_002.csv). - Ensure each file write is flushed and closed before sleep/shutdown.

- If power loss: on next boot, check your file, maybe recompute CRC for each entry, and ensure continuity.

This architecture gives you: persistent storage, frequent logging, timestamped data, and wear-safe writes.

FAQ : Common Questions & Answers

Q1. Can I just write to flash every time I get a reading?

A: You could, but it’s not ideal. Frequent flash writes without buffering can wear out your flash, reduce longevity, and slow down your system. It’s often better to buffer and batch writes.

Q2. How big can SPIFFS be?

A: It depends on how you configure your partition in ESP-IDF or with Arduino-ESP32. You choose how much flash space is allocated to SPIFFS when you flash the firmware.

Q3. Will NVS wear out?

A: NVS includes wear-leveling, but it’s not infinite. It’s good for many writes but not for extremely frequent huge binary logs. Use proper strategy or external memory if that’s your use case.

Q4. My SD card file gets corrupted when I power off. What to do?

A: Make sure to file.flush() and file.close() properly. Also, consider using journaling or two-phase writes, where you write to a temporary file and then rename when complete.

Q5. Do I need to worry about little‑endian or big‑endian issues?

A: Yes if you’re writing binary data. For logs in text (CSV/JSON), it’s not a problem. But for binary efficient logs, be consistent and document your format.

Q6. How do I know when flash wears out?

A: Flash manufacturers don’t typically let you read write-cycle counts. But during development, you can estimate how many writes you’re doing, monitor failure, or use external memory like FRAM if endurance matters.

Why This Is the Best Way My Recommendation

For most beginners, I recommend the following balanced strategy:

- Use NVS for small critical state.

- Use SPIFFS or LittleFS for structured logging.

- Buffer data in RAM and write in batches.

- Use timestamps via

esp_timer_get_time()or NTP. - Implement rolling log files to manage storage.

- Handle file errors and power loss gracefully.

This method gives you persistent data, avoids flash over-use, and is pretty easy to maintain.

If your use case is more demanding (many writes, super long-term logging), then consider external FRAM or SD card.

Real-World Example: Data Logging with ESP32 Store Data Frequently

Let me walk you through a hypothetical project, to make it more concrete.

Project: A remote environmental sensor node that logs temperature, humidity, and light every 5 seconds. It has Wi-Fi, but no constant connection. Data should survive reboots and power cuts. We want to store a week’s worth of data.

Hardware:

- ESP32

- DHT22 (temperature + humidity sensor)

- Light sensor (analog)

- SD card module

Storage Plan:

- Use the SD card to store logs — huge capacity.

- Use NVS to store metadata: last file name, number of entries, pointer.

- Use RAM buffer: every 5 samples (25 seconds), write to SD in a batch.

Software Flow:

- On boot:

- Mount SD.

- Load metadata from NVS (what was last log file, current index).

- If mounting fails or new file needed, create a new log file.

- In loop:

- Read sensors.

- Get timestamp (via NTP or

esp_timer_get_time()). - Append reading to RAM buffer.

- After buffer is full (5 entries), open file, write buffer, close file.

- Update metadata in NVS: total lines written, file index.

- If log file size > threshold (say 5 MB), start a new log file.

- Delay using

delay(5000)or similar.

- On unexpected reset:

- At next boot, continue from metadata so you don’t overwrite or lose data.

Benefits:

- Minimal wear on SD (memory cards are designed for frequent writes).

- Metadata safely stored in NVS.

- RAM buffer reduces number of file operations.

- Log files are manageable and can be transferred via SD card easily.

Advanced Tips for the More Ambitious

- Compression: If you’re storing a lot of data, compress log entries in RAM before writing (e.g., use zlib or simple binary encoding).

- Encryption: For security, encrypt your log files or blobs in NVS.

- Over-the-air (OTA): Combine storage with OTA: store previous and new firmware images in flash partitions.

- Database-like storage: Use lightweight embedded databases like SQLite on SPIFFS or SD (though heavier on code).

- MQTT upload + local backup: Stream data live to a remote server via MQTT, but also store locally as a fallback.

- Circular buffer in flash: Implement a ring buffer in external flash or FRAM, with pointers in NVS for start and end.

Common Mistakes to Avoid ESP32 Data Storage Pitfalls

- Writing too often to flash: Writing every second without buffering wears out flash quickly.

- Not closing files: Forgetting to close or flush files can corrupt SD or SPIFFS.

- No wear leveling: Using raw flash without a wear‑leveling mechanism could lead to early failure.

- Poor error recovery: Not handling corrupted files or bad sectors can crash your logger.

- No timestamping: Without real time or boot time, your logs may not be useful.

- Ignoring power loss: Not handling unexpected power cuts can mean data loss.

- Oversizing RAM buffer: Holding too much data in RAM can crash if you exceed available memory.

Summary: ESP32: Best Way to Store Data Frequently?

To sum up:

- There are multiple ways to store data with ESP32: RAM, NVS, SPIFFS, SD card, FRAM, RTC memory.

- The best strategy depends on your needs: how often you write, how much you write, and whether the data needs to survive reboots.

- For frequent but small writes, NVS is usually your best bet.

- For structured logs, SPIFFS (or LittleFS) is ideal.

- For large volume, persistent data, use an SD card.

- For very high endurance writes, external FRAM is excellent.

- For sleep-based systems, RTC memory helps maintain state across wake cycles.

By buffering data in RAM and writing in batches, you balance efficiency and endurance. Combine that with timestamping (via system time or NTP) and smart file management (rolling logs, error recovery), and you have a robust, persistent data logger.

Final Thoughts

If someone asks me: “Hey, what’s the ESP32: Best way to store data frequently?”, I’d tell them: It depends on your use case, but in many real-world scenarios, a combination of NVS for small, frequent state updates and SPIFFS or SD card for actual logs, with batch writes from RAM and good timestamping, gives you a solid, reliable, and efficient solution.

Don’t over-optimize prematurely. Start with something simple: log to SPIFFS, flush every few seconds, monitor your partition usage. As your project evolves, if you need more endurance or space, you can shift to external FRAM or SD.

Finally: test your system reset it, power it off, kill power during writes see how it recovers. That’s how you catch issues early.

Mr. Raj Kumar is a highly experienced Technical Content Engineer with 7 years of dedicated expertise in the intricate field of embedded systems. At Embedded Prep, Raj is at the forefront of creating and curating high-quality technical content designed to educate and empower aspiring and seasoned professionals in the embedded domain.

Throughout his career, Raj has honed a unique skill set that bridges the gap between deep technical understanding and effective communication. His work encompasses a wide range of educational materials, including in-depth tutorials, practical guides, course modules, and insightful articles focused on embedded hardware and software solutions. He possesses a strong grasp of embedded architectures, microcontrollers, real-time operating systems (RTOS), firmware development, and various communication protocols relevant to the embedded industry.

Raj is adept at collaborating closely with subject matter experts, engineers, and instructional designers to ensure the accuracy, completeness, and pedagogical effectiveness of the content. His meticulous attention to detail and commitment to clarity are instrumental in transforming complex embedded concepts into easily digestible and engaging learning experiences. At Embedded Prep, he plays a crucial role in building a robust knowledge base that helps learners master the complexities of embedded technologies.