Learn PCI Drivers in Linux , including PCIe architecture, BARs, device probing, interrupts, and kernel driver development.

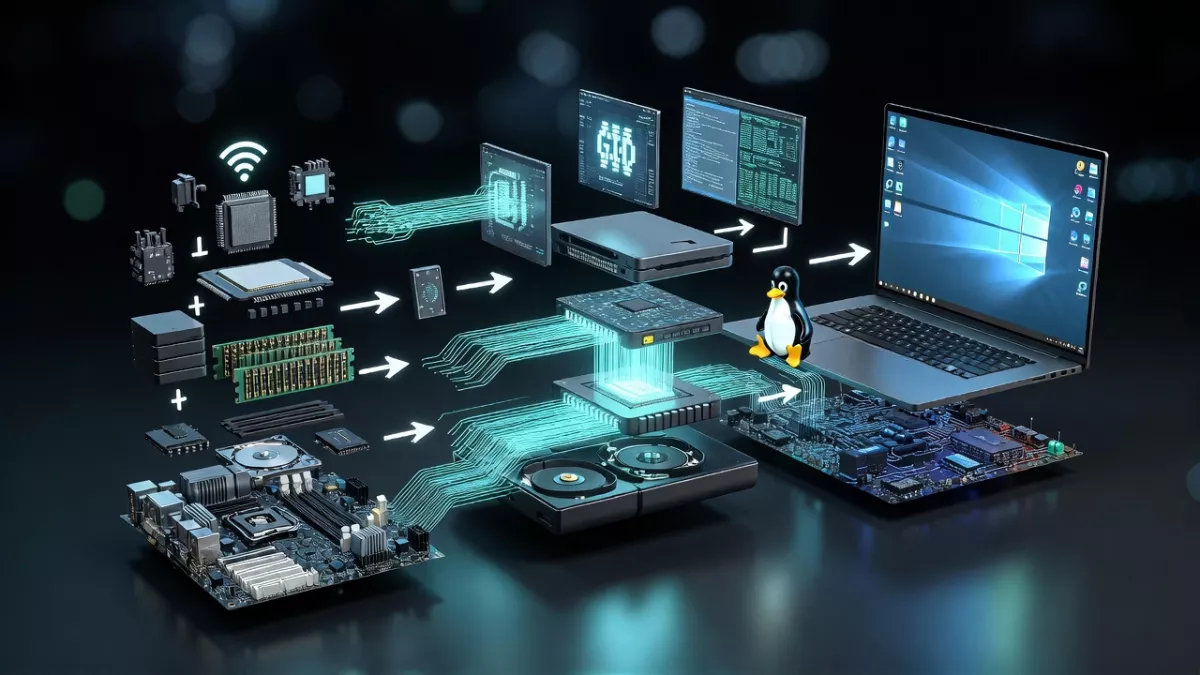

If you’re curious about how Linux talks to hardware on the PCI bus, you’re in the right place. Today we’re going to unpack PCI drivers in Linux, explain how they work, and give you hands‑on insights into writing, debugging, and maintaining them. Think of this as a conversation no jargon‑heavy press release stuff just clear, direct, smart explanations.

We’ll cover everything from the basics of PCI architecture to writing your own PCI driver, handling interrupts, using kernel APIs, and debugging in real time. Whether you’re an embedded engineer, a kernel hacker, or just passionate about low‑level Linux development you’ll find value here.

What Is a PCI Device and Why Do We Need Drivers?

Ask yourself this: when a network card, graphics card, or storage controller plugs into your machine, how does Linux know what to do with it? That’s where PCI devices and PCI drivers in Linux come into play.

PCI stands for Peripheral Component Interconnect. It’s a standard bus that lets the CPU talk to hardware devices through a uniform, discoverable interface. Each PCI device has:

- A unique Vendor ID

- A Device ID

- One or more Base Address Registers (BARs)

These BARs map device memory or registers into the CPU’s address space. The Linux kernel uses all of this information to initialize hardware and make it usable by software.

But to actually drive the device — to make it send packets, render pixels, or read data — Linux needs a PCI driver.

Why PCI Drivers in Linux Matter

You might be thinking: “Isn’t Linux just going to figure this out?” Not quite.

Hardware does not speak an agreed universal language — it has its own control registers, memory layout, protocols, and quirks. A PCI driver in Linux is the piece of software that:

- Detects the PCI device

- Allocates resources for it

- Maps its I/O or memory regions

- Hooks interrupt handlers

- Provides user‑level interfaces

Without a proper driver, the hardware sits idle. With a good driver, your system boots smoothly and performs reliably.

Linux PCI Subsystem: An Overview

Before we write code, let’s understand the ecosystem.

The Linux PCI subsystem handles:

- Device enumeration — when the system boots, it scans the PCI bus for devices

- Resource allocation — assigning IRQs, memory ranges, and I/O ports

- Driver binding — matching PCI devices to drivers based on Vendor/Device IDs

- Runtime power management

- Hot plugging (on PCIe systems)

At the core is the struct pci_driver, which defines callbacks the kernel uses to interact with your driver.

Key Structures You’ll See in PCI Drivers

Here’s a snapshot of essential kernel structs you’ll encounter:

struct pci_driver {

const char *name;

const struct pci_device_id *id_table;

int (*probe)(struct pci_dev *dev, const struct pci_device_id *id);

void (*remove)(struct pci_dev *dev);

…

};

- probe() — called when the kernel finds a matching PCI device.

- remove() — called when the device is removed or the module is unloaded.

- id_table — lists the Vendor and Device IDs this driver supports.

struct pci_dev represents the device itself — the registers, BARs, IRQs, and more.

PCI Driver Loading and Binding

When a PCI device is detected:

- The Linux kernel scans all PCI buses

- It reads each device’s configuration space

- It tries to match the device against registered

pci_drivertables - If a match succeeds, it calls the driver’s probe()

This lets your code initialize the device early in boot or when the module loads.

Writing Your First PCI Driver in Linux

Let’s get practical.

Here’s a minimal skeleton of a PCI driver:

#include <linux/module.h>

#include <linux/pci.h>

static const struct pci_device_id mypci_ids[] = {

{ PCI_DEVICE(0x1234, 0x5678) },

{ 0, }

};

MODULE_DEVICE_TABLE(pci, mypci_ids);

static int mypci_probe(struct pci_dev *dev, const struct pci_device_id *id)

{

pr_info("PCI device found: Vendor=0x%x Device=0x%x\n",

id->vendor, id->device);

/* Allocate resources, map BARs, setup IRQs */

return 0;

}

static void mypci_remove(struct pci_dev *dev)

{

pr_info("PCI device removed\n");

}

static struct pci_driver mypci_driver = {

.name = "mypci",

.id_table = mypci_ids,

.probe = mypci_probe,

.remove = mypci_remove,

};

module_pci_driver(mypci_driver);

MODULE_LICENSE("GPL");

This small driver:

- Registers itself with the PCI subsystem

- Matches a specific vendor/device

- Prints info when a device is found

You can expand this to allocate DMA memory, map IO regions, handle interrupts, and expose sysfs or char interfaces.

PCI Configuration Space: What You Need to Know

Every PCI device has a configuration space (256 bytes on classic PCI, larger on PCIe).

It holds:

- Vendor and Device IDs

- Command/Status registers

- BARs

- Interrupt line and pin

- Capabilities (like MSI or power management)

Linux provides helpers like pci_read_config_word() and pci_write_config_dword() to access this safely.

Understanding config space is essential — it’s the first step in letting your driver talk to hardware.

Memory and I/O Mapping With PCI Drivers

PCI devices have regions called BARs — Base Address Registers — that tell the OS where the device’s registers or memory are.

You use:

pci_request_regions(dev, "myname");

pci_enable_device(dev);

bar_addr = pci_iomap(dev, bar_num, 0);

This:

- Reserves the I/O or memory ranges

- Enables the device

- Maps those regions into the Linux kernel’s address space

Once mapped, you use readl()/writel() or ioread8()/iowrite8() to interact with the hardware registers.

Interrupts: IRQs, MSI, and Event Handling

Most PCI devices generate interrupts. Linux supports:

- Legacy IRQs

- MSI (Message Signaled Interrupts)

- MSI‑X (multiple MSI vectors)

In your driver, you register an interrupt handler:

ret = request_irq(dev->irq, mypci_isr, IRQF_SHARED, "mypci_irq", dev);

Your ISR should be fast, defer heavy work to tasklets or workqueues, and return quickly.

Modern drivers use MSI because it avoids shared IRQ lines and is more efficient.

DMA and PCI Drivers in Linux

For high‑speed data transfer, you’ll want to use DMA (Direct Memory Access). PCI devices often support bus master DMA.

Linux provides APIs:

dma_alloc_coherent()dma_map_single()dma_unmap_page()

This ensures memory you share with the hardware is safe from CPU caches and accessible to the PCI device.

Getting DMA right is critical for performance, especially in networking, storage, and graphics drivers.

Power Management and PCI

Modern systems can suspend, resume, and power‑manage PCI devices.

Linux offers hooks like:

pci_enable_wake()pm_runtime_enable()pci_set_power_state()

Your driver must respond to suspend/resume events gracefully so that hardware enters low power and comes back up without failure.

Error Handling and PCI

PCI supports Advanced Error Reporting (AER). Bad device behavior, master aborts, or target timeouts can happen.

Linux PCI drivers should:

- Check return values

- Use

pci_try_enable_device() - Handle I/O errors

- Reset devices if needed

Good error handling makes your driver robust and reliable on real hardware.

Hot‑Plug and PCIe

PCI Express supports hot‑plugging on some platforms.

Linux can detect and bind drivers when devices appear after boot.

You’ll need to test how your driver behaves when devices show up unexpectedly, or disappear — like in server blade environments.

Debugging PCI Drivers in Linux

If your driver doesn’t work, what tools do you use?

Here are essential ones:

1. dmesg

Kernel logs show probe messages, IRQ errors, BAR mappings, and more.

2. lspci

Shows PCI devices detected by Linux:

lspci -vvv

This reveals device class, IRQs, BARs, capabilities, and vendor/device IDs.

3. debugfs

Many PCI subsystems expose debug info here.

4. printk / pr_info

Place log statements in your driver to track execution.

5. tracepoints and perf

You can attach to kernel trace events to see what’s happening.

Effective debugging is not just about tools — it’s about understanding what success looks like for your driver.

User Space Interaction: ioctl, sysfs, and Character Devices

Your PCI driver might need to talk to user space.

Common methods:

- Character driver — exposes a

/devnode - sysfs entries — expose attributes under

/sys - ioctl — custom commands between user and kernel

Design your interface with simplicity and safety in mind.

Real‑World Example: Network PCI Driver (Simplified)

Real PCI drivers are large. But at a high level, a network PCI driver:

- Registers PCI support

- Enables device and memory regions

- Allocates RX/TX queues with DMA buffers

- Registers net_device and NAPI poll structures

- Handles interrupts and packet transmission

- Supports ethtool for statistics and features

This illustrates how PCI drivers integrate with other Linux subsystems.

Performance Tips for PCI Drivers

To make your driver fast:

- Use MSI/MSI‑X instead of legacy IRQs

- Avoid unnecessary interrupts with batching

- Use NAPI or polling for network drivers

- Cache frequently used data

- Avoid blocking calls in ISR

Efficiency matters — especially on high‑throughput devices.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Here are things that commonly break PCI drivers:

- Forgetting

pci_enable_device() - Not requesting regions with

pci_request_regions() - Ignoring error returns

- Incorrect DMA mapping

- Conflicting IRQs

Simple checks and code structure go a long way.

Testing Your PCI Driver Safely

When testing:

- Use virtual machines or hardware with risk tolerance

- Always have a way to recover when kernel panics

- Use incremental changes

- Test suspend/resume

Testing is just as important as writing good code.

Step-by-Step Implementation of a PCI Driver in Linux

Step 0: Prerequisites

Before starting, make sure you have:

- A Linux system (Ubuntu, Fedora, or embedded Linux)

- Kernel headers installed

sudo apt-get install build-essential linux-headers-$(uname -r) - A PCI device for testing or a virtual PCI device on QEMU.

- Root privileges for flashing/loading the driver.

- Text editor:

vim,nano, or IDE like VS Code.

Step 1: Understand Your PCI Device

Every PCI device has:

- Vendor ID and Device ID

- BARs (Base Address Registers) — memory or I/O

- IRQ — interrupt line

- Capabilities — like MSI/MSI-X

You can check these with:

lspci -nnv

Example output:

00:19.0 Ethernet controller [0200]: Intel Corporation I211 Gigabit Network Connection [8086:1533] (rev 03)

- Vendor ID:

8086 - Device ID:

1533

Step 2: Create Driver Skeleton

Create a directory for your driver:

mkdir ~/pci_driver

cd ~/pci_driver

Create a file called mypci.c.

Minimal skeleton:

#include <linux/module.h>

#include <linux/pci.h>

#include <linux/init.h>

#include <linux/kernel.h>

#define DRIVER_NAME "mypci_driver"

/* PCI device ID table */

static const struct pci_device_id mypci_ids[] = {

{ PCI_DEVICE(0x8086, 0x1533) }, // Replace with your device

{ 0, }

};

MODULE_DEVICE_TABLE(pci, mypci_ids);

/* Probe function */

static int mypci_probe(struct pci_dev *dev, const struct pci_device_id *id)

{

pr_info(DRIVER_NAME ": PCI device found Vendor=0x%x Device=0x%x\n",

id->vendor, id->device);

return 0;

}

/* Remove function */

static void mypci_remove(struct pci_dev *dev)

{

pr_info(DRIVER_NAME ": PCI device removed\n");

}

/* PCI driver structure */

static struct pci_driver mypci_driver = {

.name = DRIVER_NAME,

.id_table = mypci_ids,

.probe = mypci_probe,

.remove = mypci_remove,

};

module_pci_driver(mypci_driver);

MODULE_LICENSE("GPL");

MODULE_AUTHOR("KALP");

MODULE_DESCRIPTION("Sample PCI driver");

Step 3: Create Makefile

In the same folder, create a Makefile:

obj-m += mypci.o

all:

make -C /lib/modules/$(shell uname -r)/build M=$(PWD) modules

clean:

make -C /lib/modules/$(shell uname -r)/build M=$(PWD) clean

Step 4: Compile the Driver

Run:

make

You should see a mypci.ko file — this is your kernel module.

Step 5: Load the Driver

- Insert the module:

sudo insmod mypci.ko

- Check kernel logs:

dmesg | tail

You should see:

mypci_driver: PCI device found Vendor=0x8086 Device=0x1533

- List loaded modules:

lsmod | grep mypci

Step 6: Map BARs (Memory/I/O regions)

Modify probe() to request and map memory:

int bar = 0; // First BAR

if (pci_request_regions(dev, DRIVER_NAME)) {

pr_err(DRIVER_NAME ": Unable to request PCI regions\n");

return -ENODEV;

}

pci_enable_device(dev);

void __iomem *bar0 = pci_iomap(dev, bar, pci_resource_len(dev, bar));

if (!bar0) {

pr_err(DRIVER_NAME ": Unable to map BAR\n");

pci_release_regions(dev);

return -ENODEV;

}

pr_info(DRIVER_NAME ": BAR0 mapped at %p\n", bar0);

Release BARs in remove():

pci_iounmap(dev, bar0);

pci_release_regions(dev);

pci_disable_device(dev);

Step 7: Setup Interrupt Handling

- Add an interrupt service routine (ISR):

static irqreturn_t mypci_isr(int irq, void *dev_id)

{

pr_info(DRIVER_NAME ": Interrupt received\n");

return IRQ_HANDLED;

}

- Request IRQ in

probe():

if (request_irq(dev->irq, mypci_isr, IRQF_SHARED, DRIVER_NAME, dev)) {

pr_err(DRIVER_NAME ": Unable to request IRQ\n");

pci_iounmap(dev, bar0);

pci_release_regions(dev);

return -EBUSY;

}

- Free IRQ in

remove():

free_irq(dev->irq, dev);

Step 8: Support DMA (Optional for High-Speed Devices)

If your PCI device uses DMA:

dma_addr_t dma_handle;

void *dma_buf;

dma_buf = dma_alloc_coherent(&dev->dev, BUF_SIZE, &dma_handle, GFP_KERNEL);

if (!dma_buf) {

pr_err("Failed to allocate DMA buffer\n");

return -ENOMEM;

}

/* Use dma_buf for device DMA */

/* Free DMA in remove() */

dma_free_coherent(&dev->dev, BUF_SIZE, dma_buf, dma_handle);

Step 9: Enable Hot Plug / Power Management (Optional)

Add runtime PM hooks:

static int mypci_suspend(struct pci_dev *dev, pm_message_t state)

{

pr_info(DRIVER_NAME ": Device suspend\n");

return 0;

}

static int mypci_resume(struct pci_dev *dev)

{

pr_info(DRIVER_NAME ": Device resume\n");

return 0;

}

static struct pci_driver mypci_driver = {

.name = DRIVER_NAME,

.id_table = mypci_ids,

.probe = mypci_probe,

.remove = mypci_remove,

.suspend = mypci_suspend,

.resume = mypci_resume,

};

Step 10: Test Your Driver

- Load the module:

sudo insmod mypci.ko - Check

dmesg - Verify PCI BARs mapped:

lspci -vvv - Generate an interrupt (if hardware supports)

- Unload module:

sudo rmmod mypci - Ensure cleanup works

Step 11: Flash Driver for Permanent Use

Once tested:

- Copy the

.kofile to/lib/modules/$(uname -r)/extra/:

sudo cp mypci.ko /lib/modules/$(uname -r)/extra/

- Update module dependencies:

sudo depmod -a

- Add to

/etc/modulesto auto-load at boot:

echo "mypci" | sudo tee -a /etc/modules

- Reboot and verify:

lsmod | grep mypci

dmesg | tail

Step 12: Debugging and Validation

- Check logs:

dmesg | tail -50 - List devices:

lspci -vvv - Check memory mapping:

cat /sys/bus/pci/devices/0000:00:19.0/resource - Use

strace/perffor performance insights

Step 13: Optional: Expose Device to User Space

Use sysfs:

device_create_file(&dev->dev, &dev_attr_status);

Or character device:

alloc_chrdev_region(&dev_num, 0, 1, "mypci_char");

cdev_init(&my_cdev, &fops);

cdev_add(&my_cdev, dev_num, 1);

This allows applications to read/write PCI device.

PCI Drivers in Linux Interview Questions & Answers

Round 1: Fundamentals / Basic Concepts

1. What is PCI?

Answer:

PCI stands for Peripheral Component Interconnect. It’s a hardware bus standard that allows CPUs to communicate with peripherals like network cards, graphics cards, or storage devices. PCI devices are discoverable and configurable using Vendor ID, Device ID, BARs, and IRQs.

2. What is a PCI driver in Linux?

Answer:

A PCI driver in Linux is a kernel module that allows the Linux kernel to interact with a PCI device. It:

- Detects devices

- Allocates resources

- Maps I/O and memory regions

- Handles interrupts

- Exposes interfaces to user space

3. What are BARs in PCI devices?

Answer:

BAR stands for Base Address Register. It tells the OS where the device’s memory or I/O space is. PCI devices can have multiple BARs:

- Memory BAR: Maps device memory to CPU address space

- I/O BAR: Maps I/O registers

Linux uses pci_iomap() to map BARs in a driver.

4. How does Linux detect PCI devices?

Answer:

Linux uses PCI enumeration:

- Scans PCI buses on boot

- Reads each device’s configuration space

- Matches Vendor/Device ID with registered

pci_driver - Calls the driver’s

probe()function

Tools like lspci show detected devices.

5. What is struct pci_driver?

Answer:

It’s the main structure representing a PCI driver in Linux:

struct pci_driver {

const char *name;

const struct pci_device_id *id_table;

int (*probe)(struct pci_dev *, const struct pci_device_id *);

void (*remove)(struct pci_dev *);

};

probe()is called when a device is foundremove()is called on device removal

6. What is the PCI configuration space?

Answer:

It’s a special memory region (256 bytes in PCI, larger in PCIe) that contains:

- Vendor ID & Device ID

- BARs

- Interrupt lines/pins

- Capabilities (MSI, power management)

Linux drivers access it using pci_read_config_word() or pci_write_config_dword().

7. What are IRQs and MSI in PCI?

Answer:

- IRQ (Interrupt Request): A signal from device to CPU indicating an event

- MSI (Message Signaled Interrupt): Modern alternative to legacy IRQs, sent as messages via PCIe instead of shared IRQ lines

- MSI-X: Supports multiple vectors for high-performance devices

8. How do you map PCI device memory in Linux?

Answer:

- Request device regions:

pci_request_regions() - Enable device:

pci_enable_device() - Map BAR:

pci_iomap(dev, bar_num, size) - Access mapped memory:

readl()/writel()

9. What are the steps in writing a PCI driver?

Answer:

- Identify device (Vendor/Device ID)

- Create driver skeleton (

pci_driver) - Implement

probe()andremove() - Map device memory and I/O regions

- Request interrupts

- Optional: DMA setup, power management, sysfs or char device interface

- Compile, load, test, and flash

10. How can a user-space program interact with a PCI driver?

Answer:

- Character device:

/dev/mydevice - Sysfs entries:

/sys/bus/pci/devices/0000:00:19.0/ - ioctl: For custom commands

11. How do you debug PCI drivers?

Answer:

dmesglogslspci -vvvcat /sys/bus/pci/devices/.../resource- Kernel printk (

pr_info(),pr_err()) - Tracepoints (

trace-cmd,perf)

12. Difference between PCI and PCIe

Answer:

| PCI | PCIe |

|---|---|

| Parallel bus | Serial point-to-point |

| Shared bus | Dedicated lanes |

| Lower bandwidth | Higher bandwidth |

| IRQ-based | Supports MSI/MSI-X |

13. What are common pitfalls in PCI drivers?

Answer:

- Forgetting

pci_enable_device() - Not requesting regions (

pci_request_regions()) - Incorrect IRQ handling

- Memory mapping errors

- Ignoring DMA synchronization

- No proper cleanup in

remove()

Round 2: Advanced / Practical Questions

14. How do you handle DMA in PCI drivers?

Answer:

Use Linux DMA APIs:

void *buf;

dma_addr_t dma_handle;

buf = dma_alloc_coherent(&dev->dev, size, &dma_handle, GFP_KERNEL);

/* Use buf for device DMA */

dma_free_coherent(&dev->dev, size, buf, dma_handle);

DMA ensures CPU and PCI device access the same memory without cache issues.

15. What is the difference between ioremap() and pci_iomap()?

Answer:

- ioremap(): Maps any physical address into kernel space

- pci_iomap(): Convenience function to map PCI BARs; automatically uses device’s BAR info

16. How do you support hot-plug in PCIe?

Answer:

- Implement

probe()andremove()correctly - Kernel detects insertion/removal

- Optionally implement runtime PM hooks (

suspend(),resume())

17. What are common memory access functions in PCI drivers?

Answer:

readb(),writeb()→ 8-bitreadw(),writew()→ 16-bitreadl(),writel()→ 32-bitioread8(),iowrite8()→ for I/O mapped regions

18. How do you register an interrupt handler?

Answer:

request_irq(dev->irq, mypci_isr, IRQF_SHARED, "mypci", dev);

- ISR should be fast and defer heavy work using tasklets or workqueues

- Free IRQ in

remove()

19. What is MSI and why is it preferred over legacy IRQs?

Answer:

- MSI is Message Signaled Interrupts, sent as packets over PCIe

- Avoids shared IRQs

- Supports multiple vectors (MSI-X)

- Reduces CPU overhead → better performance for high-speed devices

20. How do you implement power management?

Answer:

- Use runtime PM APIs:

pci_enable_wake()

pm_runtime_enable()

pci_set_power_state(dev, PCI_D3hot)

- Implement

suspend()andresume()callbacks

21. How do you handle BARs of varying sizes?

Answer:

- Use

pci_resource_len(dev, bar_num)to get BAR size - Map BAR using

pci_iomap(dev, bar_num, size) - Always release in

remove()

22. How do you clean up on driver removal?

Answer:

In remove():

free_irq(dev->irq, dev);

pci_iounmap(dev, bar0);

pci_release_regions(dev);

pci_disable_device(dev);

Ensures no memory leaks or dangling pointers.

23. Explain pci_enable_device()

Answer:

- Enables PCI device I/O and memory regions

- Activates device and allows access to BARs

- Must call before accessing device registers

24. How to expose PCI device attributes in sysfs?

Answer:

static DEVICE_ATTR(status, S_IRUGO, show_status, NULL);

device_create_file(&pdev->dev, &dev_attr_status);

- Allows user-space read/write via

/sys/bus/pci/devices/...

25. How do you debug mapping issues?

Answer:

- Check

lspci -vvvfor BAR info - Use

dmesglogs afterpci_iomap() - Verify physical addresses in

/sys/bus/pci/devices/.../resource

26. How to test PCI driver functionality?

Answer:

- Load module:

sudo insmod mypci.ko - Check logs:

dmesg - Verify BAR mapping:

cat /sys/bus/pci/devices/.../resource - Generate device interrupts and see ISR logs

- Test user-space interface (char device or sysfs)

- Unload module:

sudo rmmod mypci

27. Difference between PCI legacy interrupts and MSI/MSI-X

| Feature | Legacy IRQ | MSI | MSI-X |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sharing | Shared IRQ line | Dedicated | Multiple vectors |

| Overhead | Higher | Lower | Lower + multiple events |

| Performance | Low-medium | High | High |

28. How does Linux match PCI devices with drivers?

Answer:

- Using

struct pci_device_idtable in driver - Kernel compares device Vendor ID & Device ID with table entries

- Calls driver’s

probe()on match

29. Common mistakes in PCI driver interviews

- Forgetting

pci_release_regions() - Not checking return values

- Mapping wrong BAR

- Not freeing IRQ

- Not handling suspend/resume

30. How do you optimize a PCI driver for performance?

Answer:

- Use MSI/MSI-X interrupts

- Batch device requests instead of frequent interrupts

- Use DMA for bulk transfers

- Avoid blocking calls in ISR

- Use workqueues/tasklets for deferred work

Pro Tip:

If asked “Explain end-to-end PCI driver development”, you can summarize:

- Identify device IDs

- Create driver skeleton (

pci_driver) - Implement

probe()/remove() - Map BARs and memory

- Setup interrupts (legacy or MSI/MSI-X)

- DMA setup if needed

- Optional: power management and hot-plug support

- Test with

dmesg,lspci, sysfs, char device - Flash module for boot auto-load

FAQ: PCI Drivers in Linux

1. What is a PCI driver in Linux?

A PCI driver in Linux is a kernel module that allows the operating system to communicate with PCI devices, such as network cards, graphics cards, or storage controllers. It handles device detection, memory mapping, interrupt handling, and provides user-space interfaces.

2. How does Linux detect PCI devices?

Linux performs PCI enumeration during boot or module load. It scans all PCI buses, reads each device’s configuration space, and matches the device’s Vendor ID and Device ID with the registered pci_driver. If a match is found, the kernel calls the driver’s probe() function.

3. What is a PCI configuration space?

Every PCI device has a configuration space, which stores information like:

- Vendor ID & Device ID

- Base Address Registers (BARs)

- Interrupt lines and pins

- Device capabilities (e.g., MSI, power management)

Linux drivers access it using pci_read_config_word() or pci_write_config_dword().

4. What are BARs in PCI devices?

Base Address Registers (BARs) specify the memory or I/O regions of a PCI device. They tell the OS where the device’s registers or memory are mapped. Linux uses pci_iomap() to map BARs into kernel virtual memory for easy access.

5. How are interrupts handled in PCI drivers?

PCI devices generate interrupts to notify the CPU of events. Linux supports:

- Legacy IRQs – shared interrupt lines

- MSI (Message Signaled Interrupts) – dedicated messages

- MSI-X – multiple vectors for high-performance devices

Drivers register an ISR with request_irq() and free it in remove().

6. How can a user-space application interact with a PCI driver?

User-space interaction is possible via:

- Character devices (

/dev/mydevice) - Sysfs entries (

/sys/bus/pci/devices/...) - ioctl commands for custom control

This allows applications to read/write device data safely.

7. What is the role of DMA in PCI drivers?

Direct Memory Access (DMA) allows PCI devices to read/write system memory without CPU intervention. Linux provides APIs like:

dma_alloc_coherent()dma_map_single()dma_free_coherent()

DMA improves performance for high-speed devices like network cards or storage controllers.

8. How do you debug PCI drivers in Linux?

Common debugging methods:

dmesg– check kernel logslspci -vvv– view device details/sys/bus/pci/devices/.../resource– verify BARs- Kernel logs with

pr_info()orpr_err() - Trace tools like

trace-cmdorperffor performance insights

9. What is the difference between PCI and PCIe?

| Feature | PCI | PCIe |

|---|---|---|

| Bus type | Parallel shared bus | Serial point-to-point lanes |

| Bandwidth | Lower | Higher |

| IRQ | Legacy shared IRQs | Supports MSI/MSI-X |

| Hot-plug | Limited | Fully supported |

PCIe is modern and faster but the driver concepts remain similar.

10. What are common mistakes to avoid in PCI drivers?

- Forgetting to call

pci_enable_device() - Not requesting or releasing device regions (

pci_request_regions(),pci_release_regions()) - Incorrect IRQ or memory mapping

- Not freeing IRQs or DMA buffers in

remove() - Ignoring suspend/resume callbacks or error handling

Read More about Process : What is is Process

Read More about System Call in Linux : What is System call

Read More about IPC : What is IPC

Mr. Raj Kumar is a highly experienced Technical Content Engineer with 7 years of dedicated expertise in the intricate field of embedded systems. At Embedded Prep, Raj is at the forefront of creating and curating high-quality technical content designed to educate and empower aspiring and seasoned professionals in the embedded domain.

Throughout his career, Raj has honed a unique skill set that bridges the gap between deep technical understanding and effective communication. His work encompasses a wide range of educational materials, including in-depth tutorials, practical guides, course modules, and insightful articles focused on embedded hardware and software solutions. He possesses a strong grasp of embedded architectures, microcontrollers, real-time operating systems (RTOS), firmware development, and various communication protocols relevant to the embedded industry.

Raj is adept at collaborating closely with subject matter experts, engineers, and instructional designers to ensure the accuracy, completeness, and pedagogical effectiveness of the content. His meticulous attention to detail and commitment to clarity are instrumental in transforming complex embedded concepts into easily digestible and engaging learning experiences. At Embedded Prep, he plays a crucial role in building a robust knowledge base that helps learners master the complexities of embedded technologies.